Was the transition from Neanderthal to modern humans delayed by the presence of the Neanderthals? Did they ever procreate?

By Nick Nutter | Updated 27 Aug 2022 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Tundra Landscape

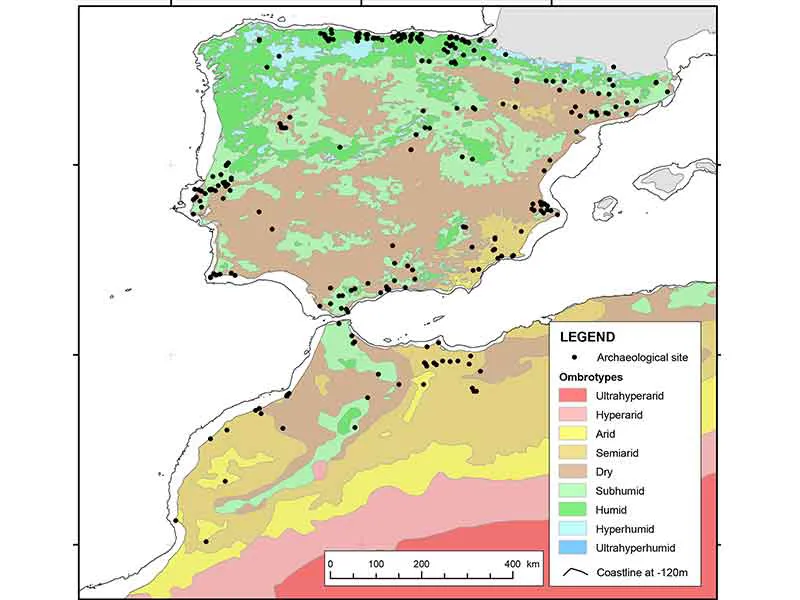

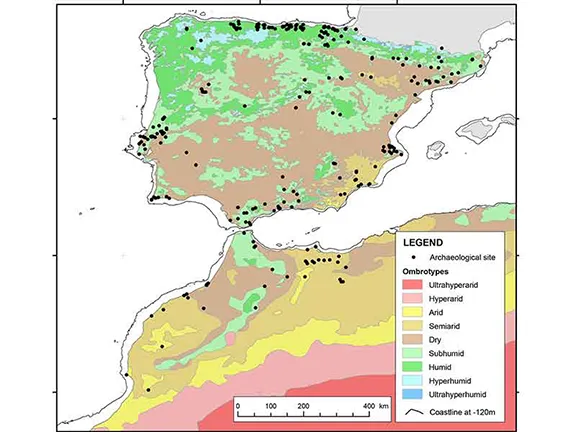

The Andalucia from which the Neanderthals were departing and into which modern humans were arriving was vastly different to that of today. An extended coastal strip, from 5 to 15 kilometres wide, caused by lower sea levels during the glaciation, ran from Gibraltar round to Almeria, with certain exceptions such as; the coast from Nerja to Almunecar, the Cabo de Gata coast, and the coast immediately north of Villaricos where the mountains fall sheer into the sea and a 120 metre drop in sea level only made the cliffs that much higher than they seem today. The coast from Gibraltar to the Algarve had an even wider coastal plain. At Europa Point, the southernmost tip of Gibraltar, cliffs fell vertically into the Mediterranean Sea. A very narrow, to non-existent plain west of Gibraltar suddenly expanded to up to 50 kilometres wide north of Tarifa up the entire length of the Costa de la Luz.

Black Pine

During the Last Glacial Period, the Iberian Peninsula, especially Andalucia, had become a refuge for plants as well as humans. Further north, beyond the Sierra Morena mountain chain that forms the northern boundary of Andalucia, the Meseta, was an inhospitable plateau of tundra - fauna and flora. These conditions were replicated in the upper parts of the Sierras that traverse Andalucia until, at altitude, ice and snow took over. At lower altitudes, below the tundra type landscape, the species seen today in the high Sierras, grew down to sea level, Quercus ilex (holm oak), and Quercus suber (cork oak), Abies (fir) and Pinus nigra (European black pine). The Pinus nigra is now fairly rare. One still exists, along with other species that survived in the lower altitudes of Andalucia, in the high reaches of the Rio Gor, in Granada province.

This somewhat bleak landscape was sometimes relieved. Many typically Mediterranean species managed to survive in isolated enclaves, for instance the olive tree, and elm, walnut and birch trees. Within those enclaves, red deer and ibex flourished along with the occasional stray reindeer from the Meseta.

That however is not the full story. The zone in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, Cantabria, is classified as Euro-Siberian during this period, whilst the Mediterranean coast was Subtropical, creating widely diverse climatic and vegetation zones over a relatively short distance from north to south. Temperature and humidity-wise, the ten millennia between 45 and 35kya was volatile. Grasses and trees, including typical Mediterranean species, other than pine, colonised areas during clement periods whilst open woodland, parkland, wooded steppe and open steppe created a mosaic of landscapes that moved around the Peninsula according to the climate and the altitude.

Modern humans first penetrated the Iberian Peninsula via the western gap between the Pyrenees and the Biscay coast. Here, along the northern flanks of the Cantabrian Cordillera they lived in caves and rock shelters. Some cave shelters such as Altamira, El Castillo, and Tito Bustillo were decorated with cave art dating back to about 40,000 BC. These early migrants brought with them a toolkit called Aurignacian.

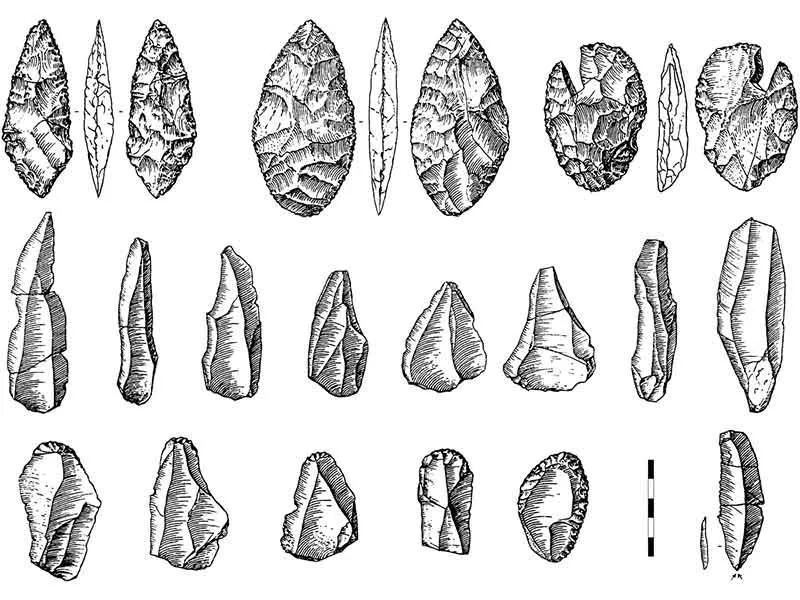

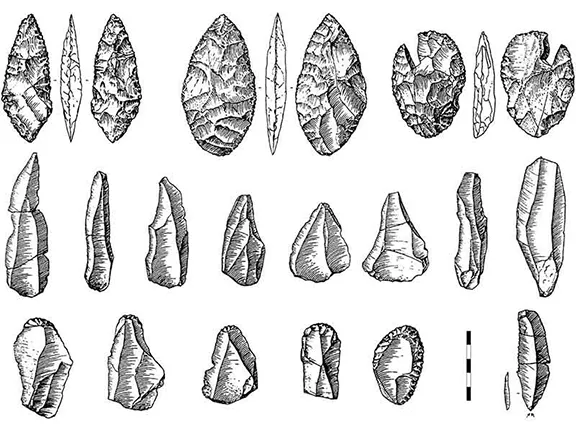

The Aurignacion Toolkit

The Aurignacian tool industry is characterized by worked bone or antler points with grooves cut in the bottom. Their flint tools include fine blades and bladelets struck from prepared cores rather than using crude flakes. However, the early modern humans entering the Iberian Peninsula were already refining their tools and dispensing with some of the Aurignacian traditions considered ubiquitous by modern archaeologists. The Venus figurines for instance, often carved out of mammoth ivory, were prevalent in Central and Eastern Europe but have never been found in the Iberian Peninsula.

Coastal plains and Climate

It took modern humans upwards of 12,000 years to populate the Iberian Peninsula and this inordinate length of time requires some explanation. One obvious reason is that the presence of Neanderthals prevented a rapid occupation. This situation was not unique, the peninsula of Italy was also a Neanderthal refuge and took a correspondingly greater length of time to occupy than areas of Europe with little or no discernible Neanderthal presence.

A second possibility is that the modern human advance was halted by the climate. A sharp climatic downturn 40,000 years ago created an arid buffer zone across the Iberian Peninsula that would have prevented modern humans in the north and west from reaching the Neanderthal refugium in the south west.

The mechanics of the occupation are still debated. DNA evidence suggests that at least some interbreeding took place but not necessarily in the Iberian Peninsula. It now looks as though there was complicated gene swopping between modern humans soon after they left Africa with archaic human populations in the Middle East and in Asia before the ancestors of those modern humans reached the Iberian Peninsula. By the time modern humans did arrive in the Iberian Peninsula, they already carried some genes from Neanderthals and from other archaic populations such as the Denisovans. Researchers have found that some of these genes were helpful, such as those involved with the production of keratin, a protein used in skin, hair and nails and genes involved with protection from the sun’s UV rays. This transfer of genes could have helped modern humans to adapt to conditions away from Africa that Neanderthals had long become accustomed to.

Châtelperronian Toolkit

There is still controversy that evidence of a shared, more advanced technique for making stone tools, known as Châtelperronian (a technique between Neanderthal Mousterian technology and the modern human Aurignacian technology), suggests communication between the two groups took place about 40,000 years ago in the vicinity of Cova Foradada at Oliva in the Valencia region. Cova Foradado is also the site of the most complete Neanderthal skeleton found to date in the Iberian Peninsula in 2010 and a 37,000 year old eagle talon necklace. Work is progressing to date the skeleton.

Archaeological evidence indicates that Neanderthals were living in the south of the Iberian Penisnsula, in ever decreasing numbers until about 28 kya. The evidence also suggests that the extreme southwest of the Iberian Peninsula, modern day Andalucia, became their last stronghold. The caves showing the latest evidence of a Neanderthal presence in the Iberian Peninsula are; Carihuela Cave in Granada province which is 100 kilometres inland on the northern flank of the Sierra Nevada, Zafarraya which is 25 kilometres inland from the coast at Velez Malaga, Ardales cave which is 55 kilometres from the coast at Malaga, Nerja in Malaga province and Gorham’s Cave on Gibraltar that are both on the coast.

During the 12,000 years it took modern humans to trek through the Iberian Peninsula there were at least 9 climatic fluctuations, sudden colder snaps in an already chilly climate. From warmer peak to warmer peak, in some cases was less than 1000 years. The Neanderthal record disappears entirely, between 28 and 24 kya, coincident with a severe cold snap.

During these colder periods, Neanderthals retreated south. As the weather became more clement modern humans, with their better child survival rate, hunting efficiency and social connections, and ability to use technology to combat inclement weather, such as make more efficient, insulatory clothing, moved into the vacated territory before the Neanderthals had built up enough numbers to move back to the areas they had abandoned. Each time there was a cold snap, a little more territory would be lost, and dispersed bands of Neanderthals would become isolated in pockets separated by mountains, eroding their overall viability. Once established, it seems that modern man was more capable of adapting to variations in climate. Interestingly, modern research is indicating that Neanderthals did sometimes live in the colder, northern parts of Europe during the cold snaps. Whether they were strictly temporary inhabitants making seasonal forays into colder areas, with a metabolism better able to cope with the cold, or permanent residents has not yet been ascertained.

Ancient hunter gatherer populations are reckoned to require an average of 60 square kilometres per person. A band consisting of 12 – 30 individuals would need between 720 and 1,800 square kilometres. In favoured areas this would be a little less, in unfavourable areas, a little more.

The hunter gatherer’s nirvana is a mixed landscape of wooded craggy high ground for game, valley sides for tubers, fruit and nuts and a river or an estuarine or coastal environment for fish and shellfish.

Areas favoured by Neanderthals would also be looked upon by modern humans as good areas to be as they were all hunter gatherers. As the Neanderthals retreated to the southwest, even with a depleting population, their numbers became more concentrated into smaller areas creating more competition for dwindling resources and for the incoming modern humans.

The hunter-gatherer ‘code of conduct’ should also be taken into account because it applied as much to Neanderthals as it did to modern humans. This equalitarian, ‘help thy neighbour’ approach would help explain the lack of any archaeological evidence for conflict at this time and what appears, archaeologically, to have been a seamless transfer of ownership.

These explanations could account for the perceived archaeological time delay between the last Neanderthal levels and evidence of the first modern human, particularly at sites such as Gorham’s Cave on Gibraltar.

The possible routes taken by modern man should also be considered because those routes became the first communication channels. Socially, these first modern hunter gatherers lived most of the year within their own band of 12 to 30 people. Food was shared and there would have been little or no sense of personal ownership. These individual bands were tied, culturally and socially, with other bands. At certain times and presumably, places, bands would congregate in order to increase the choice of mating partners. These meetings would be the opportunity to exchange information, skills and materials. These were the first networks, delineated connections that, due to the low density of the hunter gatherers, spread over long distances, despite overland mobility being pedestrian.

We have already seen that some of the earliest records of the presence of modern man is cave art, along the Cantabrian Cordillera. They also left some of their Aurignacian tools in El Castillo, Cueva de Morin and La Vina, in Cantabria, dated to 42-40 kya. From the eastern end of the Cordillera, a route southeast, down the Ebro river, takes you to the Mediterranean coast at Catalonia where Aurignacian tools have been found at L’Arbreda and Romani, again dated to between 42 and 40 kya.

A second route southwest from the eastern end of the Cordillera, takes you into the River Duero valley and thence to the Atlantic. From the Atlantic coast, easy coastal routes take you down the full length of Portugal with a diversion up the Tagus valley. The Duero valley residents would then be in close proximity in the next valley to the north. The dates for Aurignacian assemblages found in Portugal are currently under review. One exciting development, reported in 2015, is a potential overlap of Mousterian and Gravettian (a tool industry that developed from the Aurignacian) tools dated to 34 – 32 kya, at Foz do Enxarrique in southern Portugal.

From the Mediterranean coast at Catalonia, a coastal route can be followed to just south of Murcia. Aurignacian tools dated to 34.5 kya have been found at Les Mallaetes in Valencia and at Cova Foradada near Alicante there is evidence of Aurignacian activity at two levels corresponding to 40 kya and 35 – 31 kya.

Currently there is little evidence for Aurignacian presence in Murcia, which brings us to the eastern reaches of Andalucia roughly 30,000 years ago. The lack of evidence may be due to the arid conditions referred to above. As the climate became warmer and wetter, the last vestiges of aridity would have been in Murcia and what is now the province of Almeria in Andalucia. In fact, large parts of Almeria are classified as semi arid zones to this day.

Here the situation becomes interesting. The Neanderthal’s final stronghold was a wide strip down the coast of Andalucia that extended up to 100 kilometres inland at the eastern end down to 2 kilometres at Gibraltar. It appears as though modern man initially ignored this triangle and diverted inland, heading west to the Cordillera Subbeticas and then southwest down the northern flanks. Only later would he venture into what had been, exclusively, Neanderthal territory. The central Meseta was neatly bypassed, and it would be some time before this inhospitable tundra region was populated.

Whilst this route and timeline seems logical and in accordance with the evidence so far, it is by no means fixed in stone. A study carried out in Bajondillo Cave (Torremolinos, Malaga province) published in 2019, indicates that modern humans with their Aurignacian tools were established there between 45,000 and 43,000 years ago. It is difficult to explain this very isolated, early, occurrence. We shall return to this issue at the end of this article.

By about 25,000 BC, modern humans were the sole occupants of the Iberian Peninsula. The population levels would have been similar to that of the departed Neanderthals during their heyday, about 1,200 square kilometres for each band of 12 - 30 individuals. With a land area of 87,500 square kilometres, the overall population of Andalucia could have been about 1,500. However, not all of Andalucia was populated during this early hunter gatherer phase. Archaeology has failed to find much trace of modern hunter gatherers in the Guadalquivir valley itself, or the Sierra Morena mountain chain that forms the northern border of Andalucia. It could be that the latter was too cold, being adjacent to the central Meseta, and the former did not support the range of food required by a healthy hunter gatherer band, except on its southern and eastern margins, the foothills of the Cordillera Subbetica. In any case the land area actually occupied amounted to about a third of the overall area, reducing the potential population in Andalucia, to just 500 people, the lower limit for the number of people required to reproduce in a genetically viable group.

A study published in 2011 claimed to show that, at the time of the transition from Neanderthal to modern human, there was a tenfold increase in the population. Whilst this is likely to be an exaggerated claim it does give some credence to DNA and skeletal studies now coming to light that indicate that late Neanderthals were breeding with close relatives, a habit known as consanguinity. Published in 2019, a study of 50,000 year old skeletal remains of Neanderthals from El Sidrón cave in Asturias, Spain, shows evidence for consanguinity. The team identified 17 bones, belonging to at least 4 individuals, showing congenital abnormalities. These are conditions present at birth, as opposed to ones developed during life through injury, infection or nutritional deficiencies. In the El Sidrón remains, the congenital features included cleft or asymmetric vertebrae, a misshapen kneecap and a baby tooth retained into adulthood. The identified conditions are rare in living humans and may be harmless, but they do occur more frequently in cases of inbreeding. In other words, these skeletal features suggest the parents were kin. Consanguinity could be a result of a reduced population resulting in a lack of suitable breeding partners.

El Sidrón cave also provided evidence of a more sinister insight into late Neanderthal family life. Later excavations found the remains of 12 individuals, three adult males, three adult females, three adolescent males, two juveniles and one infant. Researchers found that the genetic diversity of the group was lower than would be expected for non-related Neanderthals. All three of the adult males carried the same mitochondrial lineage whereas the adult females carried different lineages. The males must have shared the maternal lineage whilst the females were brought in from other Neanderthal families. It seems as though female Neanderthals took up residence with their male partners whilst the males stayed in the family home.

All the individuals had suffered from stunted growth, presumably arising from malnutrition, as well as the problems caused by consanguinity. Their end was as unhappy as their lives. Many of the bones had been cut with stone tools or smashed open for the marrow indicating that they had been killed and eaten. Was this a starving family turning on itself or a competing family desperate for food? We shall never know. However, one thing we can be reasonably sure of is that modern humans had no part to play in the tragedy since they had not yet arrived in the area.

Adapting to the climate forced modern humans to adopt new strategies to survive. They did this by inventing new types of clothing. Bone needles appear during the early part of this period, used for stitching together leather and fur garments. Leather and fur shoes or boots, evidenced by changing morphology of feet, became a necessity. It is likely that light, transportable shelters were also used to augment more permanent bases in caves and rock shelters. They developed more efficient hunting methods to such a degree that many of the larger game animals started to disappear from the archaeological record. Deer, horses, ibex and aurochs became less populous although research suggest that none became totally extinct in the Iberian Peninsula. Even so, humans were forced to develop methods of catching smaller game, rabbits, hares and game birds. Nets, traps and snares were invented, and it is likely that the woven basket was first used to make the collecting of tubers, fruits and nuts easier. These strategies allowed the young and elderly to take part in the food gathering routine. It is also likely that women may have started to become differentiated by an association with lower risk forms of meat acquisition, food gathering and the manufacture of shelters and clothing.

Blades and bladelets were used to make decorations and bone tools from animal remains. Tools developed, blunt-back knives, tanged arrowheads and boomerangs. It is also thought that oil lamps made of stone appeared during this period, the fuel being rendered animal fat. The whole ensemble is usually referred to as the Gravettian culture. It did not suddenly appear overnight, the overlap between Aurignacian and Gravettian lasted as long as the Gravettian did in some instances, but it can safely be said that the innovative and clearly recognisable parts of the Gravettian were in place soon after modern humans entered Andalucia.

It may be imagined that, as each innovative idea or product was tried and tested, the techniques and skills would slowly move backwards and forwards, up and down the communication networks, passed from hand to hand and mouth to mouth. It could take many generations for an idea formulated at one end of the chain to percolate through to the other end, many hundreds, even thousands of kilometres away. In the meantime, improvements would be made that would in turn pass through the system. This capability for notional communication whilst far apart was a key factor in the survival of modern humans. Sometimes links in the chain were lost and an arm of the network was cut off. This is what happened about 20,000 BC, close to the last glacial maximum, communication with Europe east and north of the Pyrenees was lost and the two areas developed in slightly different ways.

Let us not forget the last of the Neanderthals. They too continued to change, at least culturally, during their final few thousand years in the Iberian Peninsula. The hash marks found at Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar, the paintings at Ardales Cave and the eagle talon necklace found at Cova Foradado all indicate they were developing artistically. They could also of course have been developing their tools, either independently or as a result of assimilation of ideas from modern humans; the Châtelperronian that produced denticulate stone tools and also a distinctive flint knife with a single cutting edge and a blunt, curved back, is suspiciously similar to the Gravettian toolkit. Interestingly, the principle area for so called Châtelperronian tools is just around the Pyrenees corner from Valencia and Catalonia, along one of the communication channel networks.

As the Neanderthals finally depart from Andalucia during an intense cold period during the Last Glacial Maximum, it is worth noting that the skeletal remains of modern humans from this early period (found elsewhere, the record of finds from Andalucia at this time is bleak), it seems as though these first modern humans were tall, up to 190 centimetres, with heavy musculature, particularly to the legs; a gracile figure inherited from their ancestors in Africa. Over the thousands of years of the remaining glaciation, modern humans became squatter and shorter, their bodies adapting to the cold. By 25 kya, any observer would have been hard pressed to differentiate between a modern human and a Neanderthal.

Whilst the Châtelperronian tools remain a speculative cargo along the networks, another set of tools most certainly are not. Without so much as drawing breath, the Gravettian merged into the Solutrean south of the Pyrenees. The dividing line is usually set at 25,000 BC, just after modern man became sole proprietor of Andalucia and at the start of the Last Glacial Maximum.

Finally, returning to Bajondillo Cave, Torremolinos, and the anomalous finds dating to 45 to 43 kya mentioned earlier. Across the Gibraltar Strait, in North Africa, in the Maghreb region, during this precise period when temperatures fell rapidly and then recovered just as rapidly, modern humans were experiencing a crisis. Links between the two major habitable areas, the Maghreb and Cyrenaica further east, had been cut. The climatic conditions resulted in an arid expanse between the two areas. Even in those two areas, populations were dwindling to the point of invisibility. It is possible that the northern shore across the Strait, only 6 kilometres wide during this time, with a couple of islands to act as stepping-stones, could have looked like a haven. It is inconceivable that the two groups were not aware of each other, at six kilometres even small fires at night are easily visible, although there is to date no evidence of communication. The concentration of Neanderthals then occupying Gibraltar could well have 'encouraged' any immigrants to try their luck 120 kilometres further down the coast at Torremolinos. The Aterian people of North Africa, named after the stone tool industry, used tanged and leaf shaped tools very similar to the Aurignacian tools wielded by their modern human counterparts in Europe.

If the Bajondilla Cave dates are accurate then, whether the tools were carried there from North Africa or by people migrating into the Iberian Peninsula from Europe, the small group responsible for them do not appear to have survived the long winter.

We leave the Iberian Peninsula about 25 kya. The Neanderthals have been and gone and modern humans have managed to establish a fragile toe hold in preferred areas around the perimeter of the central Meseta.

Benazzi, S.; Douka, K.; Fornai, C.; Bauer, C.C.; Kullmer, O.; Svoboda, J.F.; Pap, I.; Mallegni, F.; Bayle, P.; Coquerelle, M.; Condemi, S.; Ronchitelli, A.; Harvati, K.; Weber, G.W. (2011). "Early dispersal of modern humans in Europe and implications for Neanderthal behaviour". Nature. 479 (7374): 525–528.

Banks, W. E.; d'Errico, F.; Peterson, A. T.; Kageyama, M.; Sima, A.; Sánchez-Goñi, M. (2008). "Neanderthal extinction by competitive exclusion"

Galván, B.; Hernández, C. M.; Mallol, C.; Mercier, N.; Sistiaga, A.; Soler, V. (2014). "New evidence of early Neanderthal disappearance in the Iberian Peninsula". Journal of Human Evolution. 75: 16–27

Jean-Jacques Hublin. The earliest modern human colonization of Europe (2012) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Aug 2012, 109 (34) 13471-13472; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1211082109

Mellars, P.; French, J. C. (2011). "Tenfold population increase in Western Europe at the Neandertal-to-modern human transition". Science. 333 (6042): 623–627

Miikka Tallavaara, Miska Luoto, Natalia Korhonen, Heikki Järvinen, and Heikki Seppä (2015) Human population dynamics in Europe over the Last Glacial Maximum

Ríos, L, Kivell T. L, Lalueza-Foxv C. et al (2019) Skeletal Anomalies in The Neandertal Family of El Sidrón (Spain) Support A Role of Inbreeding in Neandertal Extinction

Stringer, C (2012). "What makes a modern human". Nature. 485 (7396): 33–35.

Stringer, C. (2016). "The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150237.

Sankararaman S, Patterson N, Li H, Pääbo S, Reich D. The date of interbreeding between Neandertals and modern humans. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(10):e1002947. doi:10.1371/ journal.pgen.1002947

Wolf, D.; Kolb, T.; Alcaraz-Castaño, M.; Heinrich, S. (2018). "Climate deteriorations and Neanderthal demise in interior Iberia"

To read the full pdf with all images and maps click here