The Romans exploited the rich mining areas near Rio Tinto in Huelva province from the 1st century AD. They literally moved mountains. The mines can be visited and the small museum demonstrates how the mines were exploited.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 14 Sep 2022 | Huelva | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

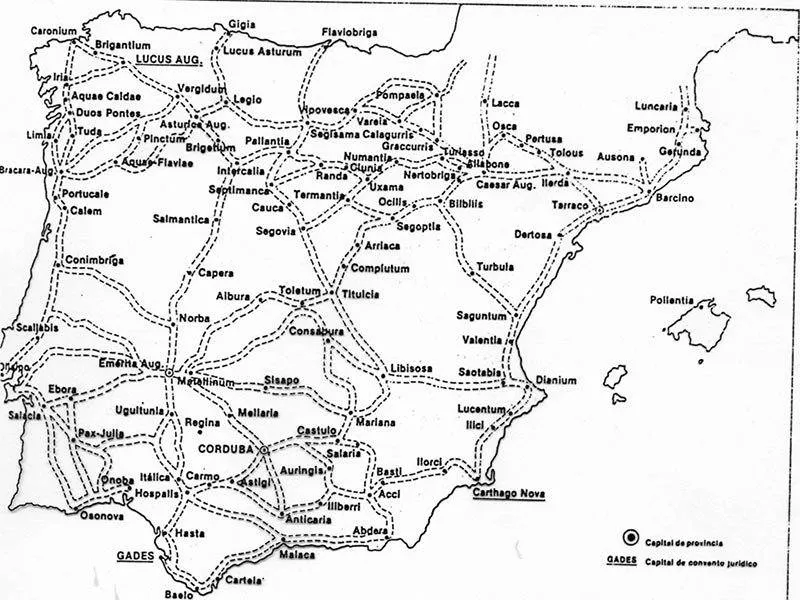

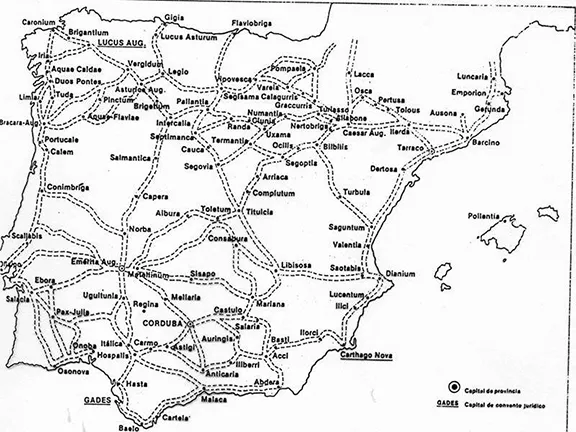

Spain, in particular the area known as Andalucia was unique in the territories conquered by the Romans in that from their first arrival they physically occupied the land. Soldiers, as they were paid off, elected to remain in Hispania rather than go back to Rome, particularly during the 1st Century BC when the political situation in Italy was anything but stable. It is during this period that references to the Roman province of Baetica first appear. Baetica roughly covers the area now known as Andalucia. The other two provinces were Lusitania, corresponding to Portugal and Extremadura and Hispania Tarraconensis that covered the rest of modern Spain.

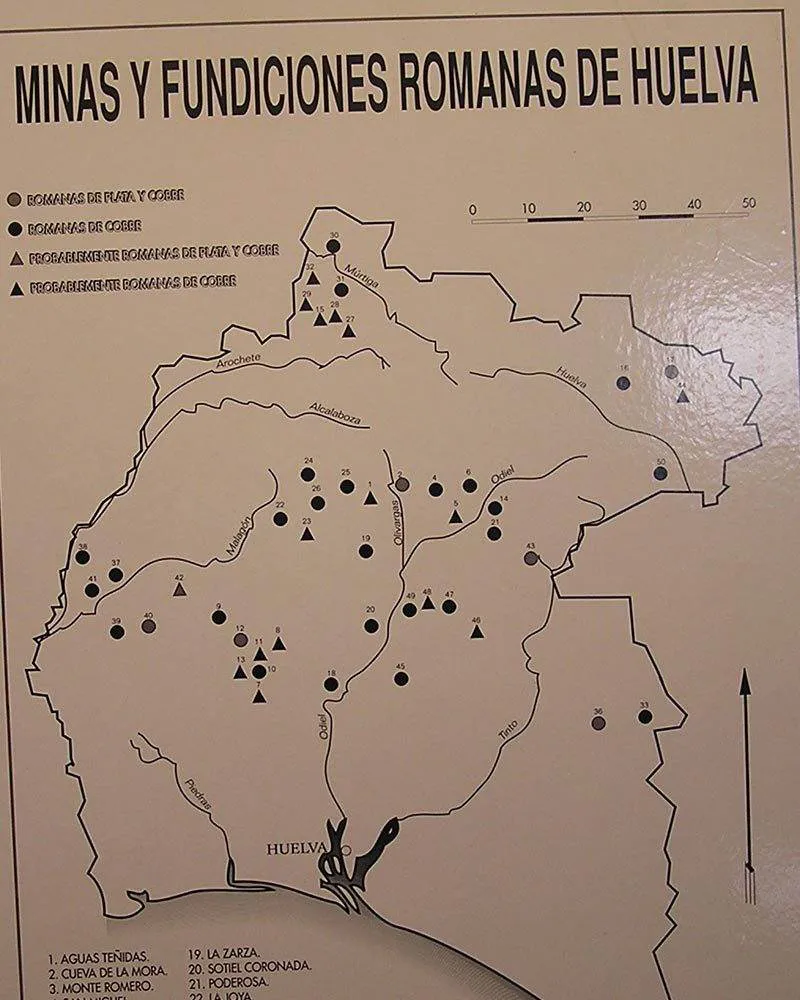

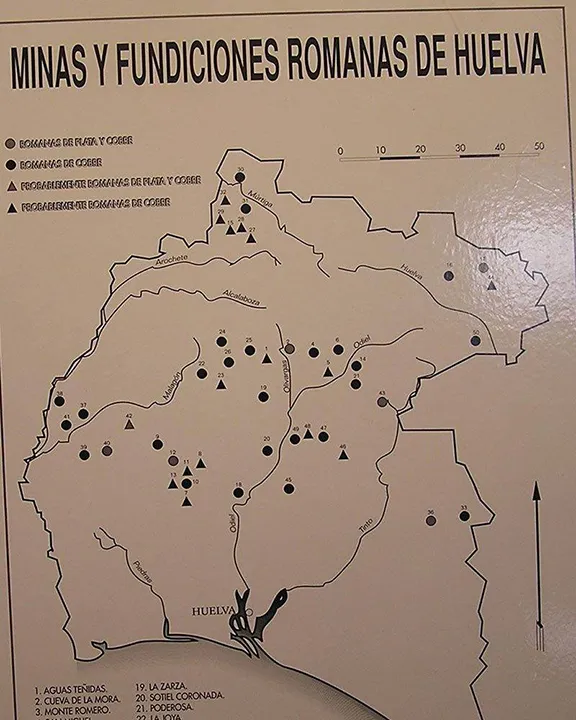

When the Romans arrived the mines were already old having already been exploited for about 2,000 years but even so only a small amount of the available ore had been removed. The original miners had found colourful ores outcropping on the surface, typically in the Rio Tinto area, green malachite, and blue azurite, both oxidised ores of copper. They had used primitive bone tools and fire to extract the ore until further extraction was impossible. Normally this left a scar. Infrequently a small shaft was made rarely more than a few metres deep and very rarely there would be evidence of small side galleries off the shaft. In the Sierra Morena there are hundreds, possibly thousands of these primitive workings. Even digging such a shallow mine was dangerous but at least the miner had the option of stopping when he judged it too hazardous. The Romans changed all that. Within a few years they had over 50 working mines within 100 kilometres to the west and north of the Rio Tinto mine itself working with typical Roman efficiency.

Roman towns in Spain

The last century BC and the first century AD saw a large increase in Romanised development of existing settlements like Gadir (Cádiz) and the establishment of coloniae which conformed to a Roman model of what constituted a town. The model was based on the city of Rome. The number of coloniae established in Baetica is a matter of considerable academic dispute but, coloniae or not, the ‘model’ was implemented at Corduba (Córdoba), Hispalis (Seville), Astigi (Ecija), Itucci (Martos), Ucubi (Espejo), Urso (Osuna), Hasta Regia (Asta), Italica (Santeponce), Iliturgi (Mengibar) and Asido (Medina Sidonia).

Roman Mines in Huelva province

Roman strategy in Baetica had been partly dictated by the presence of the rich mines in the Sierra Morena area. Prior to their occupation of Spain, Rome had been buying copper, gold and silver from Phoenician and Carthaginian traders who in turn were trading with the Tartessians in whose territory the mines were. Rome could be looked upon as a black hole as far as wealth was concerned. Its population, or at least the prosperous ones, were reputed to be extravagant, flamboyant and idle, spending their days in pleasurable, depraved and expensive pursuits, each trying to out do the others and spending huge amounts of money in the process. This depravity, particularly during the later part of the Roman period, is often cited as a major cause of Rome’s demise. That may be correct but what undoubtedly happened is that Rome bled its territories white through punitive taxes that in turn caused unrest amongst the native population. The mines would have been considered a great asset. The manner in which they were exploited is an education to the contrasting sides of Roman nature and the mines of the Rio Tinto area are a perfect example. When the Romans started mining, during the 1st century AD, the deep quarry seen in the image above was a hill.

Roman slave in water wheel

The mines were efficient because the Romans had slaves, mainly natives who had made the mistake of supporting the wrong side, and their attitude to them would, today, be considered abominable. Slaves had no rights whatsoever. A slave owner could punish or kill his slaves with no fear of retribution, he could work them to death and that is exactly what they did at Rio Tinto.

Slaves were born and lived their entire lives underground, never seeing daylight. Not that they were likely to live that long, cave ins and, as the shafts were dug deeper, sudden flooding, were regular occurrences. Technology was employed to make extraction of the ore easier and more efficient, not to safeguard the workers. In the 19th Century, at the Rio Tinto mine a series of water wheels was found in man made galleries that were used in Roman times to take water from tens of metres below the surface, up nine levels to an adit that drained the water out onto the hillside. Slaves turned the wheels. Incredibly an Archimedes screw was also used to raise water from the depths. The Archaeological Museum at Huelva displays the original wheel found at Rio Tinto in its foyer.

It was only much later in the occupation period that the Romans realised that the supply of slaves was declining to dangerous levels. They immediately, almost overnight, reversed their policy of inhumanity and slaves suddenly found that they had shorter working hours, were provided with decent food and living accommodation and could enjoy holidays. It has been estimated that when the mines closed as the Romans departed, the slaves actually enjoyed better conditions than 20th Century coal miners in the UK, Arthur Scargill would have been impressed.