The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition was established in 1478

By Nick Nutter | Updated 8 Mar 2022 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Nobody Expects the Inquisition

‘Even while I breathed there came to my nostrils the breath of the vapour of heated iron. A suffocating odour pervaded the prison. A deeper glow settled each moment in the eyes that glared at my agonies. A richer tint of crimson diffused itself over the pictured horrors of blood. There could be no doubt of the design of my tormentors. Oh, most unrelenting! Oh, most demoniac of men! 'Death,' I said, 'any death but that of the pit.’ These words were written by Edgar Allan Poe in his notorious indictment of the Spanish Inquisition, ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’. The Spanish Inquisition, the ‘Black Legend’, wicked simply because it was Spanish. Is it possible at so far remove to separate the fact from the fiction, and did anybody really expect the Spanish Inquisition?

An Inquisition

The name Torquemada, Queen Isabella’s confessor and sometime Inquisitor General, is still used to scare children, a Spanish bogeyman if you like. Yet Fernando de Valdés is hardly ever mentioned.

On the silver screen, swashbuckling melodramas set during the era of the Inquisition featuring characters like Erroll Flynn, upright, handsome, compassionate, brave, Anglo supermen with light complexions and mid brown hair, saving the blonde damsel from the clutches of the evil, greasy haired, swarthy complexioned Latino. The sub text here is the battle between Protestantism and Catholicism but movie moguls like to keep the plot simple. They were capitalising on deep seated prejudices that had been carefully cultivated over a long period of time, so long in fact that they became an integral part of a culture that was exported to America with the very Protestant settlers on the Mayflower.

So what is the truth about the Spanish Inquisition? Common sense tells us that it lies somewhere between two extremes and that to understand it there must also be an understanding of the politics of the time and the way in which people, from kings, queens and popes right down to the humble peasant thought and, as we delve deeper into the subject, how propaganda was used to influence those thoughts. As we shall see, spin-doctors are not a phenomenon of the 20th Century.

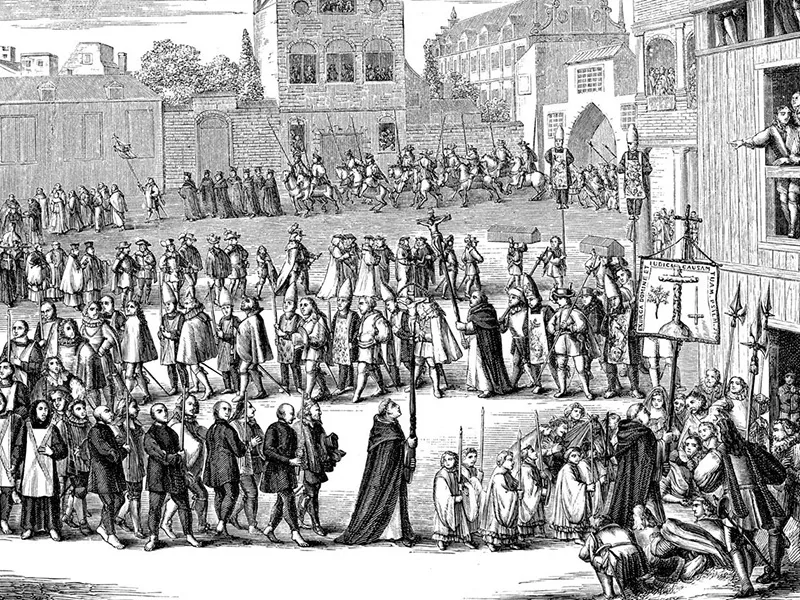

Auto de Fe

In recent years the problem faced by both scholars of the Inquisition and thinking lay people is how to reconcile the reality of the Inquisition, a deliberate programme against first Marranos (nominal converts to Christianity from Judaism) then Conversos (true converts to Christianity from Judaism), Jews and then Muslims, with ‘Convivencia’, an ideal bred from the perception of religious tolerance between Muslims, Jews and Christians, during the first 400 years of Muslim rule in al-Andalus. Convivencia reached its heights of tolerance during the Caliphate of Córdoba period, 929 – 1031 AD. A political reality during the 21st century favours Convivencia over Inquisition. Even now, scholars and politicians are working to bring the 10th century Convivencia out of the realms of idealism into a perceived reality, to reconcile a contradiction that has bedevilled the Spanish for 600 years.

The Spanish Inquisition was established in 1478 and was abolished by decree on the 15th July 1834 by the Spanish queen regent Maria Cristina de Borbón, sufficient time for any prejudices to become self-evident facts that required no evidence in order to substantiate them; but were those facts correct?

We are fortunate that the course of the Inquisition, each and every trial, each and every verdict over a period of almost four hundred years, was carefully chronicled by the Inquisitors, more carefully than any event previously and many since.

In 1478 Isabella and Ferdinand, anticipating the eventual unification of Spain, applied for a papal rescript to establish a Holy Office, an Inquisition. They used the precedent of the functioning of the Roman Inquisition during the 13th Century that was designed to quash the Cathari, a group of people whose Manichaean beliefs were inspired by a prophet called Mani, a Persian, and whose beliefs were seen as a threat to the civil as well as ecclesiastical wellbeing of the Romanised populations of southern France and northern Italy. Circuit courts were set up and over a period of 100 years the Cathari were eliminated or driven underground.

In arguments to the Pope, Ferdinand and Isabella emphasised their desire for a religiously united country, a desire with which the Pope obviously empathised. They seem to have failed to mention their other motivations that we will come to in the next episode.

It is difficult today to appreciate how people living in non Muslim parts of Europe during the Middle Ages thought. In their minds there was no distinction between Church and State. Pope Sixtus IV, in granting Ferdinand and Isabella’s request stated that it was ‘the first duty of kings to nurture and defend the faith of their people’ and followed this with a statement that was a truism in its day, ‘that no society could exist without religious uniformity’, despite the fact that the Muslims in Spain had fairly convincingly proved the contrary.

The eventual Muslim failure in al-Andalus was hailed by some as proof that the truism was correct and that the same would happen to a newly united Spain, if that ambition were ever achieved, if steps were not taken to unite the state under a common religion as well as flag.

It was not only those of the Catholic faith that believed this. Protestant Queen Elizabeth I of England firmly believed Sextus and ruthlessly persecuted Catholics during the 16th Century, the Dutch Calvinists in the Netherlands similarly barbarically persecuted anybody who did not share their beliefs.

The organisation of the Inquisition reflected the emergence of the concept of the nation-state with an emphasis on centralization and royal control, a point not lost on Sextus and succeeding popes who variously considered the Inquisition a serious undermining of their ecclesiastical authority.

In Spain, king Ferdinand, with only the nodding approval of the pope, appointed the Grand Inquisitor. He appointed five members of the High Council over which he presided. The High Council had numerous clerics responsible for recording all proceedings and consultants who debated and decided disputed questions and views. There were, by the mid 16th century, nineteen lower inquisitorial courts in Spain and more in Spanish territories in the New World and Italy. The lower courts had to submit annual general reports and monthly financial reports and could not set up an auto-de-fe without the sanction of the High Court. The auto-de-fe was the religious public ceremony that included the punishment of convicted heretics and the reconciliation of those who recanted.

This system of control is still observed today. In the UK, Parliament devolves authority to local authority, court cases can be heard by local magistrates, Crown Courts, Courts of the House of Lords and those of Appeal with the final arbiter being the Home Secretary. Centralization is a fact of life throughout the ‘civilised’ world.

What contributed to making the Inquisition alien to British minds then and now was the procedure. In Britain, in the 15th century, there was already a strong tenant of Common Law, actions that were universally accepted as being crimes even though they were not written down. Habeas corpus, the right of every individual to be brought before a court if they considered themselves wrongly convicted and the presumption that an accused was innocent until proven guilty strengthened civil liberty in countries that had a corpus of Common Law. In the 15th century, only Britain observed Common Law. Today only countries that were once part of the British Empire have common law jurisdictions or a variant of it. The writ of Habeas Corpus was only available in Britain during the 15th century and is today only available in Canada, Japan, Pakistan and the United Kingdom.

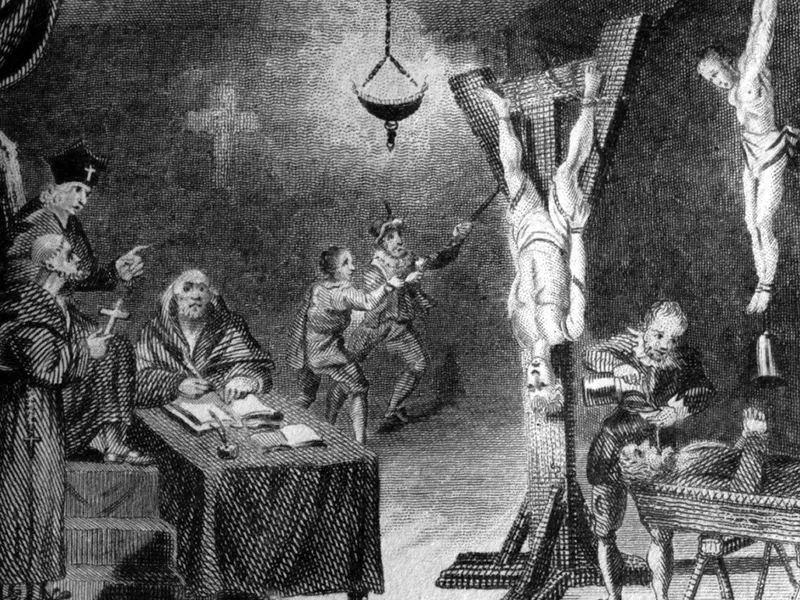

Spain was and is not a Common Law or Habeas Corpus country, you therefore must prove your innocence if accused. In Spain, during the Inquisition, the legal process started with a sworn denunciation by an individual. The accused then normally enjoyed a thirty day ‘term of grace’. This period was to allow the accused to recant or prepare a defence. The defendant was provided with a lawyer and two disinterested priests had to be present at any examination by officers of the court. The identity of the accuser was not revealed to the defendant, which was a severe disadvantage although there were severe penalties for those proved to have made a wrongful accusation. Judges decided questions of fact and law and the Inquisition combined the procedures of investigation, prosecution, and judgement. Torture was used to extract the truth. The rules stated that torture should not be that extreme that it threatened life or limb and Pope Sextus was deluged with complaints on this matter. The records show that his remonstrations to Isabel and Ferdinand fell on deaf ears.

Further reading and references

Hale, M. The History of the Common Law of England, and An analysis of the civil part of the law

Pollock and Maitland. The History of English Law before the Time of Edward I

Ray, M. (2020) Timeline of the Spanish Inquisition Encyclopædia Britannica

Ryan, Edward A. (2020) Spanish Inquisition Encyclopædia Britannica