El Argar was the first State in the Iberian Peninsula from 2200 BC to 1550 BC

By Nick Nutter | Updated 5 Mar 2022 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Castellon Alto near Galera in Granada province

From the start of the Neolithic period in the Iberian Peninsula, archaeologists have tended to create ‘cultures’ to explain the appearance of customs, funerary rituals, styles of pottery, building styles, social divisions and so on. The subdivision of a period of time into such cultures does, sometimes, give the impression that one ‘culture’ stopped, and another started whereas in actuality there was often considerable overlap. It must also be remembered that the people that made up one culture, a few generations later, were often the same people that made up the next culture. On occasion the impetus for the new culture was provided by newcomers to the area, but not always. Sometimes the new culture was home grown. One such culture that is sandwiched between the culture of Los Millares and that of the Iberians, is the Argar culture. The Argar ‘culture’ existed between about 2200 BC and 1500 BC and is a distinctive combination of skills, funerary rituals and social order that is readily identifiable as different to anything that went before. El Argar is often nowadays considered to be the first true state to appear in the Iberian Peninsula so, for that reason I will refer to them as Argarians or the Argar people and their society as Argarian.

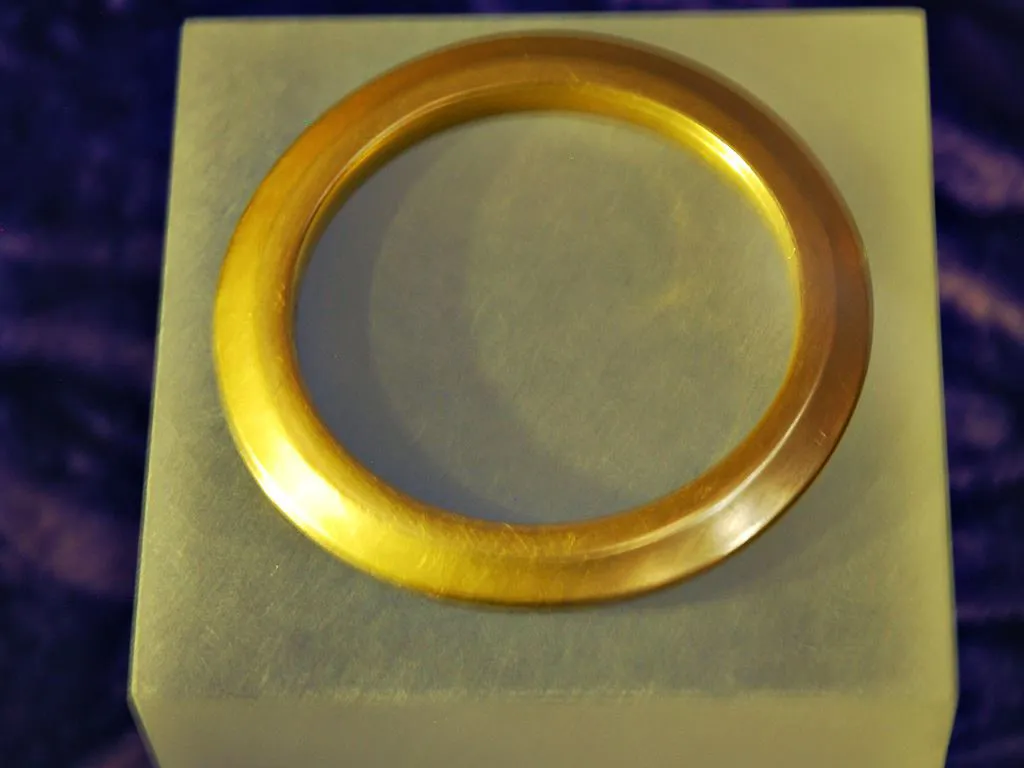

Gold bracelet from Fuente Alamo

In terms of when the Argarian society prospered. Historians place their appearance at the end of the Copper Age and the beginning of the Bronze Age which in itself implies a boundary where no such boundary exists. The transition between using solely copper and using bronze, or at least using a type of bronze that consisted of copper with impurities such as arsenic that did indeed make the copper less malleable, and eventually manufacturing true bronze consisting of copper and tin, was gradual and took place at different times and places within the Iberian Peninsula and even at different times and places within Andalucia.

From their foothold on the Murcia coast, established about 2200 BC, the Argarians expanded until about 2000 BC by which time they occupied a thin strip of land, about 30 kilometres deep, that extended from the coast just west of present-day Cartagena, 30 kilometres inland to the municipality of Pliego and then south west about 70 kilometres to the Mojácar municipality in Almeria and inland to somewhere near Arboleas, establishing a core area in the Vera basin.

Between 2000 BC and 1700 BC, their area of influence grew rapidly along the coast west as far as the present-day border between Granada and Málaga provinces, northeast as far as Alicante and inland to cover the copper and silver deposits in the eastern end of the Sierra Morena, a land area of over 33,000 square kilometres.

Ivory from North Africa

The Argarian society became known for its intramural burial practices, that is, burials that took place within a building, normally the dwellings. Human remains were placed in stone cists, large pottery urns, pits, and so-called covachas, artificial caves cut into the bedrock, with one, sometimes two and exceptionally three or more individuals placed within. While similar burial customs are well known from the eastern Mediterranean and the Balkans, they were, between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC, unique in the Iberian Peninsula.

Equally outstanding are the grave offerings placed in some of these burials, including a limited set of metal weapons, tools and ornaments, as well as highly standardised and finely burnished clay vessels, which have been classified according to eight basic shapes. Some of these pottery vessels are unknown outside the Argarian territory, such as the chalice shaped cup or goblet. On the other hand, no other society in western Europe at this time placed such a high number of copper–based halberds and swords, as well as silver diadems and other ornaments in funerary contexts.

Analysis of the grave goods in individual graves, and the position of the graves in the hierarchy of the settlement (with the ‘elite’ occupying the uppermost dwellings, commoners in the middling levels and ‘serfs or slaves’ at the bottom), revealed a strict social hierarchy. Around 1950 BC, the higher social positions became hereditary, as witnessed by an increase in infant burials with grave goods.

Los Millarian Pithoi - decorated

From early Argaric times, access to metallurgy, copper and silver, seems to have been restricted to certain settlements and the higher social groups. The concentration of rivetted tools and weapons, knives, awls, halberds and swords, is much greater in the southeast of the Peninsula than elsewhere. Moving outwards from the Argarian territory southeast there is a corresponding drop in numbers of such items found. The majority of these finds have been dated to between 1900 and 1500 BC. The dispersal of small numbers of, in particular, Argaric tanged daggers, in the northern parts of the Peninsula indicate a widespread land-based trading network.

Utilitarian Argar pottery

Around the same time as signs of hereditary leadership appear, 1950 BC, it appears as though the leaders managed to gain control of cereal production and possibly textile manufacture. This is surmised from the increased number of storage structures constructed, together with a concentration of grinding equipment in the vicinity of the warehouses and the increased production of grinding tools and weaving looms.

Only about 25% of the total population lived in the settlements. The remainder occupied scattered homesteads dedicated to agriculture, livestock breeding and producing raw materials.

It has been shown that the demographic profile of the Argarian society was remarkably young. Although some people lived to be over 60 years, the upper limit of life expectancy was nearly 40 years of age for men, and somewhat less for women, perhaps as a consequence of the risks during pregnancy and labour. The individuals who survived the childhood illnesses suffered from diseases associated with age, workload and the diet, such as degenerative osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, traumatisms, enthesopathy, caries, periodontitis, abscesses, and dental calculi. As may be expected, the elite lived longer and were in better health than the lower ranks.

There were great differences between genders mainly regarding constitution, height, muscle development, and injuries by anatomical region, inferring a difference in work organisation by sex. The occurrence of more trauma than in earlier periods and their greater frequency in males seem to fit with the general increase of social violence.

The Argaric society had a clear division of classes that became more rigid as time passed. It maintained a rigid hierarchical structure, as shown in their grave goods. For the first time, the social status was established from childhood. You were born into the ruling class, the commoners, or you were a servant or slave.

Without pre-empting the narrative to follow, it is worth outlining the social strata.

The Elite

At the top of society, there was the dominant class, comprising men initially armed with halberds or short swords and from 1800 BC onwards with long swords, presumably used to deter the population from any attempt at rebellion against the established social order. Some women were members of these powerful groups and are buried with headbands and, usually, silver adornments. The women were also buried with a knife and awl, which seems to demonstrate their relation to specific tasks. Women, men, and children of the ruling class show off valuable bronze, silver and gold ornaments. The practice of burying children of all ages started about 1950 BC. The inclusion of valuable grave goods in these burials indicates notions of heredity, not just property, but position in society as well. The funeral offerings in all high ranking burials also include high quality pottery. The use of Argaric cups seems to have been restricted to the elite classes.

Commoners

From about 1800 BC, there is a social class formed by commoners - subjects with social rights - who are guaranteed much better living conditions than the class below them. Its members are in charge of certain productive tasks, as well as helping to subjugate the rest of the population. Men belonging to this class were buried with daggers and axes and the women with a knife and awl. The funerary offerings for both sexes could include adornments, usually made out of bronze, but never made of gold. There is also an abundance of pottery containers from everyday use.

Serfs and Slaves

At the bottom of the social pile were the serfs and slaves whose remoteness from the higher classes seems to have become increasingly marked with the passing of time. Members of this class were buried without offerings or, at most, with a pot, adornment or simple tool.

The Argarian Society reached its peak in terms of building technologies, pottery production, metal working and organisation within the society about 1750 BC, at the limit of its outward expansion period. Extensive research and study at the Argarian sites enable us to present a reasonably detailed view.

References and further reading

Caramé, Manuel & Díaz-Zorita Bonilla, Marta & Sanjuán, Leonardo & Wheatley, David. (2010). The Copper Age Settlement of Valencina de la Concepción (Seville, Spain): Demography, Metallurgy and Spatial Organization. Trabajos de Prehistoria. 67. 10.3989/tp.2010.10032.

Díaz, María & Ramos, Ruth. (2018). La cosecha de El Garcel (Antas, Almería): estructuras de almacenamiento en el sureste de la península ibérica. Trabajos de Prehistoria. 75. 67. 10.3989/tp.2018.12204.

Hinz, Martin & Schirrmacher, Julien & Kneisel, Jutta & Rinne, Christoph & Weinelt, Mara. (2019). The Chalcolithic–Bronze Age transition in southern Iberia under the influence of the 4.2 ka BP event? A correlation of climatological and demographic proxies. 10.12766/jna.2019.1.

Lull, Vicente & Rihuete, Cristina & Micó, Rafael & Risch, Roberto. (2013). Political collapse and social change at the end of El Argar.

Murillo-Barroso, Mercedes & Bartelheim, Martin & Cortés, Francisco & Onorato, Auxilio & Pernicka, Ernst. (2012). The silver of the South Iberian El Argar Culture: A first look at production and distribution. Trabajos de Prehistoria. 69. 293-309. 10.3989/tp.2012.12093.

Olalde, Iñigo & Brace, Selina & Allentoft, Morten & Armit, Ian & Kristiansen, Kristian & Rohland, Nadin & Mallick, Swapan & Booth, Thomas & Szécsényi-Nagy, Anna & Mittnik, Alissa & Altena, Eveline & Lipson, Mark & Lazaridis, Iosif & Patterson, Nick & Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen & Diekmann, Yoan & Faltyskova, Zuzana & Fernandes, Daniel & Ferry, Matthew & Reich, David. (2017). The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of Northwest Europe. bioRxiv.

Risch, Roberto. (2014). The La Bastida fortification: new light and new questions on Early Bronze Age societies in the western Mediterranean. Antiquity. 88. 395-410. 10.13140/2.1.2131.0082.

Risch, Roberto & Lull, Vicente & Micó, Rafael & Rihuete, Cristina. (2015). Transitions and conflict at the end of the 3rd millennium BC in south Iberia. 10.13140/RG.2.1.3881.1286.

MUSEO DE GALERA. Guía Oficial Septiembre de 2007