Esparto grass in Andalucia from the Neolithic to the British involvement in the 19th century

By Nick Nutter | Updated 5 Mar 2022 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Esparto grass in Granada province

Esparto grass! Living in Andalucia, it is easy to take esparto for granted. Every small town ethnographic museum proudly displays artefacts manufactured from esparto grass. Esparto sandals - espadrilles, baskets and bonnets, floor coverings and fly screens may be purchased in artisan shops in villages, bulls heads and elephants, woven from esparto, are available from interior design showrooms. References to esparto crop up in unexpected places. More esparto, by bulk, was carried on the Great Southern of Spain Railway line than marble. In the first part of the 19th century, British investors put money into esparto plantations in the middle of Granada province. In 1837, a patent to manufacture paper from esparto was registered in England and the resulting product is hailed as the major reason for a massive increase in literacy in the UK. During a visit to the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid back in 2014, I saw what was supposed to be the oldest esparto grass basket to be found in Spain, something over 7000 years old and found in Cueva de los Murciélagos, Albuñol, Granada. I did not then realise the significance of the find, or attach much importance to what is, in effect, a roadside weed. My interest was finally sparked when I read about an accident on the aforementioned Great Southern of Spain Railway Company line at Huercal-Overa in 1929. Apparently thirteen wagons piled high with esparto grass caught fire. There is obviously more to this grass than meets the eye.

Donkey panniers - esparto

Esparto grass, Stipa tenacissima, is native to southern Spain and north Africa. It has properties that distinguish it from other grasses. For instance, it makes a good rope, highly prized by ancient traders. The Phoenician ship, wrecked at Mazaron about 650 BC, had an anchor rope made of esparto.

The Phoenicians no doubt discovered that the locals here in Andalucia were well aware that esparto made a great fly screen, fantastic baskets and hard wearing sandles. Esparto mats had been used as floor coverings since Iberian times.

The Roman legions were issued with esparto water canteens, esparto containers waterproofed with pitch pine resin. An example is on display at the archaeological museum at Cartagena. In any case the esparto water canteen had been in use by local shepherds for millennia before the Romans arrived.

Phoenician esparto basket

Esparto baskets were used extensively in the home and in the workplace. The mats used in the olive presses were made from esparto. From Roman times right through to the beginning of the 20th century, ore, taken from the mines, was taken to the surface by hand in esparto baskets. There it was put in esparto carriers lashed to the sides of donkeys and taken to the nearest port. Goods of all descriptions were transported to markets in esparto containers. There was hardly any aspect of life on which esparto did not have an impact. There is an exhibition at the Castillo de San Juan de los Terreros (Almeria province) displaying some of the multifarious uses to which esparto grass was and is put including items of clothing. Otzi, the iceman dating back to about 3200 BC, found mummified in the Alps, was wearing a grass cape and using grass for insulation in his shoes. He knew the water repellent qualities of plaited grass.

Roman esparto products

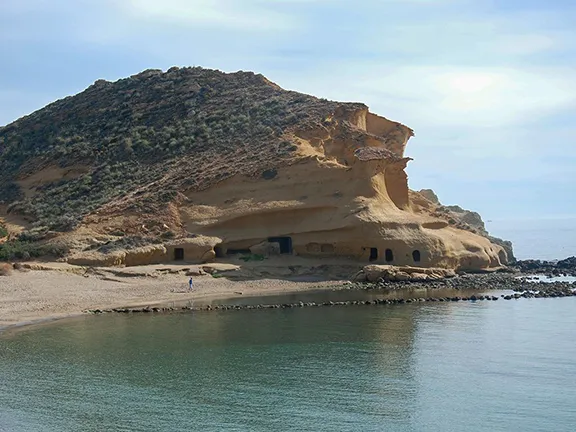

Esparto grass has different properties depending on how it is treated before use. Once harvested, the leaves can be left to dry in the sun. The result is a warm, golden brown colour known as raw esparto and it is used for everyday basketry. Crushed esparto, used for more prestigious items, is made by soaking the grass in water for about a month after which it is dried and then crushed. Eons ago, the esparto growers found that soaking the grass in fresh water tended to turn the esparto black, whilst soaking it in sea water bleached the grass so that it turned white. The process of soaking the grass in seawater and then crushing it is known as ‘cooking the grass’ and it took place up and down the Andalucian coast. There are a number of bays that were traditionally used for this purpose including Playa Los Cocedores (Almeria province) where a dam was built in shallow water to retain the grass whilst it soaked.

After treatment the blades of grass are plaited. There are dozens of plaiting techniques using anything from five to thirty-one strands at a time. The plaited esparto is then woven. Traditionally, working esparto was not an industrial scale process. It was one of the many skills passed down through each family and practised in the home. A true cottage industry. And so it would have remained if not for some entrepreneurial Brits in the early 19th century.

Playa Cocedores, Almeria

The first half of the 19th century in the UK is sometimes regarded as ‘The Age of Literacy’. There was growing public demand for the right to be able to read and write and parents were demanding that right for their children. The culmination of this trend was the Education Act of 1870 that set the framework for the public schooling of all children between the ages of five and twelve.

Meanwhile, people were reading increasingly voraciously; books of plays, stories and poems, penny novels and the early newspapers were creating a need for more paper. The first of the great Victorian authors, Charles Dickens, the Bronte sisters, Anthony Trollope and Lewis Carroll were becoming hugely popular. In 1800, every member of the UK population was responsible for the use of 2.5lbs of paper per year. By 1850 that figure stood at 8 lb per capita per year. The paper industry could not produce enough paper.

In the late 18th, early 19th centuries, paper was made from rags and they became in short supply. A similar situation had occurred in the mid 18th century and laws had been passed forbidding rags to be taken out of the country following the so called ‘rag wars’.

In 1837, a UK patent was granted for a process that would make paper from esparto grass. The grass gradually became a major export for Andalucia.

Esparto grass arriving in London c 1921

Most esparto grass grown commercially came from Granada province, in the vicinity of Cortes de Baza, Cullar and Benamaurel and in the semi-arid regions of Almeria such as the Cabo de Gata. The harvested grass was taken by donkey, ox and horse carts via unmade and sometimes unpassable tracks, to the coast where it would be loaded onto coastal trading ships and taken to Garrucha (Almeria province, Andalucia) or Aguilas (Murcia region) where it would be transhipped onto cargo boats for onward transportation to London and other European destinations.

In 2015, the people of Carboneras, a small port at the northern end of the Cabo de Gata in Almeria province, erected a statue to commemorate the esparto industry. The esparto industry was for more than a hundred years, a source of income and livelihood for many inhabitants of Carboneras. Women and men collected esparto in the mountains and accumulated it in bundles that were later stored in the "esparto warehouse", located next to the Puntica beach in the town. Twice a week, steam boats arrived at the beaches of Carboneras to transport the product via Garrucha or Águilas, to the United Kingdom and other European countries.

Between 1830 and 1850, the Scottish and English paper mills began a frenetic commercial expansion in the south of Spain and North Africa in search of the raw material and Aguilas emerged as the centre of the esparto storage and shipping industry, primarily because it already had trading links with Algeria, another major source of esparto grass.

The demand for esparto grass continued to grow. The major problem for the end users was the inefficient, and therefore expensive, manner in which the grass was taken from the plantations in Granada and Almeria to the major ports. The coming of the railway was to change that situation.

In 1866, anticipating the Great Southern of Spain Railway between Baza and Aguilas, a contract was made between Robert Cheney Johnston and Miguel María José Carvajal Tellez de Giron, Duke of Abrantes y Linares, Count of Águilar, to farm esparto grass on a 27 square mile estate in Cortes de Baza. The estate was only 18 kilometres from the eventual location of Baza station and 20 kilometres from the proposed station at Caniles. In 1867 and 1868, Johnston contracted for the use of warehouses in Aguilas and his esparto grass was exported by the Esparto Trading Company Ltd, founded in 1868. By 1887 Britain was importing 50,000 tons of esparto through British owned companies based in southern Spain.

The initial entrepreneurs had to wait until the 16th December 1894 before the railway line reached Baza. In 1920, the Great Southern of Spain Railway alone carried 31,000 tons of esparto grass to Aguilas.

The export trade in esparto grass continued until after the Second World War but then declined as its place was taken over by plastics and other fibres. One family firm that refused to give in is that of Perez y Perez in Porcuna, in northern Jaen province and they are now enjoying a revival in all things esparto.

Their products are a far cry from the humble espadrille. They work with fashion houses and stores throughout Spain creating textured lamps and matting, furniture, curtains and umbrellas. Perez y Perez products are taking America by storm, helped by the ‘organic’ and ‘vegan’ credentials of the raw material.

Meanwhile, traditional esparto grass products continue to be made in the small towns and villages in Granada and Almeria and the inhabitants of Chirivel in Almeria province, after many years of deliberation and negotiation, have successfully opened what is billed as ‘the first museum in the world dedicated to esparto grass.’

During the research for this article I found many other references to esparto; folk tales and the reminiscences of people who still remember the esparto trade, unusual uses for this versatile grass and more. In a world concerned about using renewable resources I suspect that the esparto story has a few chapters to run.