On the same day that Cantoria station opened, the 11th June 1894, the line as far as Purchena, a further 15 kilometres was inaugurated.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 25 Aug 2022 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Tijola station

On the same day that Cantoria station opened, the 11th June 1894, the line as far as Purchena, a further 15 kilometres was inaugurated. Purchena station is now restored as a restaurant. In its day it was a busy little station with locally produced marble and talcum being shipped out on the GSSR. It is also the place where our likeable roque, Don Fortunato Fernández, makes his appearance, but first a little background.

Brown coal

One of the problems facing the GSSR was the quality of the coal they were obliged to use. Coal, to fuel the steam engines, had to be transported from northern Spain. It was not the best coal in the world, in Lancashire it would have been called brown coal. It burnt quickly produced lots of flames, excessive smoke, piles of ash and little heat. For many years the Spanish Government insisted that 95% of the coal used on the railways should be coal mined in Spain.

The GSSR preferred, if possible, to use Welsh coal. One of the biggest investors in the GSSR was one David Davies MP who was a Welsh colliery owner as well as the builder of Barry Docks and The Barry Dock Railway.

In addition, he and Edmund Sykes Hett, the founder of the GSSR and major shareholder in the ill fated Hett, Maylor & Co. Ltd. were co-directors of The Ocean Coal Co.

Welsh coal arrived at Aguilas on ships that would then load up with goods that had arrived at Aquilas dock via the railway.

Welsh anthracite

Don Fortunato was a bit of a character. He wore all his wealth as jewellery and paraded around in a ‘dandy suit’ and English leather leggings.

He chose his moment, after the line had been completed, to announce that his land, on which Purchena station now stood, had beneath it a rich seam of coal and asked for six million pesetas compensation, roughly 7 million Euros in today’s money, an insignificant amount according to Fortunato, considering the quality and quantity of the coal.

He called his mine ‘Terrible’ that may have given the GSSR a clue as to the veracity of the claim.

There was a legal system set up by which mine owners could claim compensation under such circumstances. In fact, the GSSR had a fund set aside to pay compensation awarded.

Both the claimant and the GSSR tried to beat the system by employing assessors to determine the value of the minerals that had become unavailable to the mine owners by the presence of the railway line and its buildings.

Each would choose the most favourable report, the GSSR the lowest value report and the claimant the highest value report. The claim would then be hammered out in court.

Having successfully made his claim, Don Fernández dug an adit. He then obtained some coal from GSSR supplies and dumped it at the end of the adit. You can imagine him at dead of night with a wheelbarrow.

An assessor duly took samples from the adit. The results revealed two fundamental mistakes that Fortunato had made. The first mistake he made was to claim that he had coal on his land. There is no coal in Almeria, at least none has yet been discovered, apart from Don Fortunato’s. The second related to the provenance of the coal. The report stated it was identical to coal from Cardiff. Needless to say, Don Fortunato Fernández and his Terrible mine lost the case before it ever went to court.

However, whether the GSSR considered the claim so hilarious and cheeky, or whether they preferred mentions of coal from Cardiff to be kept as quiet as possible, is not known.

What is known is that they gave Don Fortunato four thousand pesetas, say 4,400 Euros in today’s money, as final settlement of his claim.

Fortunato was by no means the only person to claim significant sums of money from the GSSR for loss of mineral rights. Some of the claims became very acrimonious and took years to settle.

We can now move 10 kilometres up the line to Tijola where we can look at another problem the GSSR faced, hard water.

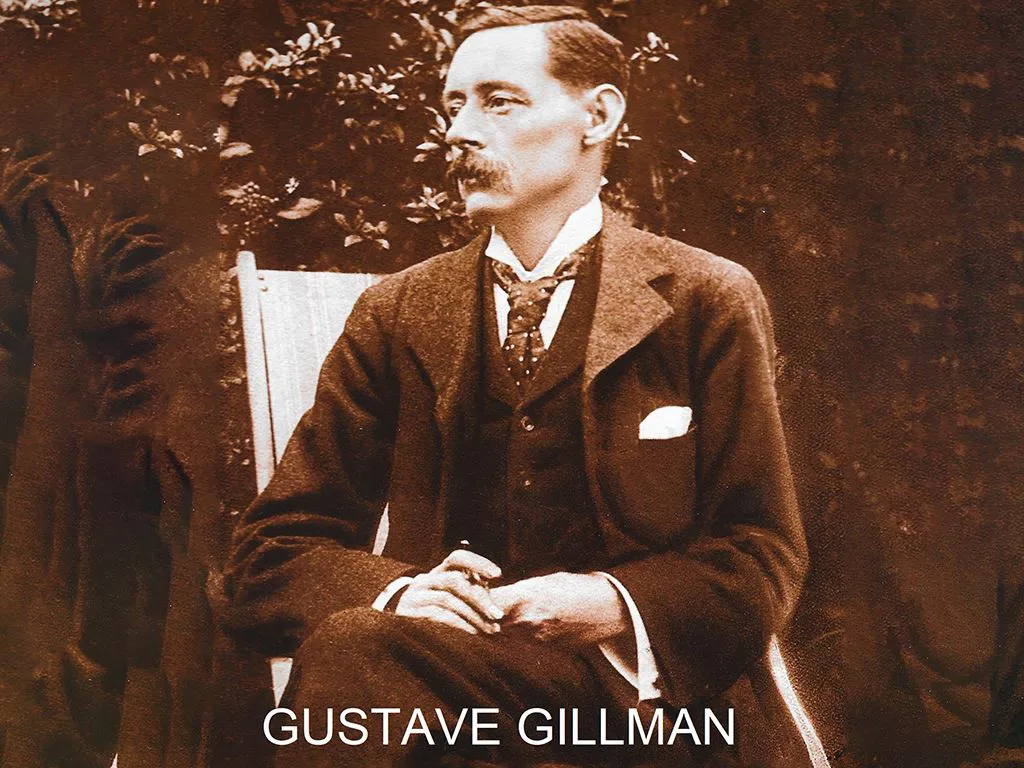

Gustave Gillman

Tijola station opened only 3 months after Purchena, in September 1894.

Tijola is important because, for the first time, the GSSR had access to water that did not cause the water pipes in the boilers to calcify and in some cases explode. It is worth looking at the water problem from the beginning.

The GSSR knew from the outset that water is a key commodity on a railway. There has to be enough of it and it has to be ‘soft’. Hard water is full of minerals that crystalise out in the water pipes and boilers causing them to fur up or calcify.

Before even bidding to construct the line, the GSSR employed assayers in Madrid and London to determine the quality of the water at any point along the proposed route of the railway. They all came back with reports that the water was good and abundant, painting a picture of a veritable Garden of Eden. It must have been quite a surprise when the first engineers arrived to find they were expected to build a railway through a semi arid zone with little available water and what was available was very hard.

As soon as the first engines started running there were always two locomotives out of action between Almendricos and Águilas.

There were always 6 or 8 boilers under repair: and after they had been repaired and remounted onto a locomotive the result was that, a few kilometres down the line they became railway watering cans, producing large puddles every time that they stopped. The need to repair leaking tubes became so frequent that the engine drivers and firemen of the GSSR were considered to be top experts in the subject.

The opening of the line from Almendricos to Huercal Overa had been eagerly awaited because there was supposed to be a supply of good soft water at Huercal Overa. According to the analysis report it was going to be the salvation of the railway. Imagine the disappointment when this water turned out to be as hard or harder than any they had so far used.

And so it went on, the more engines they had working the line, the more was spent on their upkeep.

The situation reached a climax on the 14 September 1907 when the boiler of No 2 engine, (LORCA) exploded. The accident happened on the stretch between Purchena and Tíjola. Both the driver and fireman were killed.

Water purifiers, brought in from Britain, alleviated the problem somewhat but even they calked up after purifying enough water for just two engines.

The size of the ore trains was reduced from twelve ore hoppers to nine with no noticeable increase in engine performance.

Here we introduce for the first time, the hero of this story, Gustave Gillman who started working for the GSSR in 1897 as the station manager at Aguilas station. He is best described as a restless genius, no problem on the line escaped his attention even though many were outside his area of responsibility and he became a roving trouble-shooter.

A survey had been carried out in all the valleys and one source of good, soft water had been found.

The Bacarese river that carries snow melt down from the Sierra de Bacarese, a mountain range a few kilometres south of Tijola.

Unfortunately the rights to the only soft water in the Almanzora valley had been the subject of legal disputes continuously for four hundred years. When Gustave consulted the local solicitor to enquire about the possibility of tapping into this supply, the solicitor almost fell off his chair laughing.

A solution was eventually reached whereby the GSSR were given permission to sink a well near the headwaters of the Bacarese river. A steam pump sent out from Glasgow was installed and, on the 24th August 1911, soft water started running to the Tíjola tanks. A 76mm pipeline ran from Tíjola to Zurgena, where there was a 300 cubic metre tank, thus additionally supplying water to Purchena, Fines-Olula, Cantoria, and Almanzora.

After some years, on the 1st June 1911, The GSSR installed a seawater distillation plant at Aguilas that ran for many years, closing in 1922.

The stations north of Tíjola had water delivered in a tanker by rail.

The next station up the line, Seron, opened the same day as Tijola and gave access to the iron ores from the Sierra Filabres. We will be re-acquainted with our hero there.