History of mining in Jaen Province Andalucia British companies in Linares and La Carolina

By Nick Nutter | Updated 19 Mar 2022 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Mine in Linares

Hugh James Rose arrived in Andalucia in 1873 as a chaplain working for British, French and German companies that were exploiting the lead mines of the Sierra Morena. In his description of Linares details stand out, such as "the dirt, the constant noise as much at night as in the day, the taverns and the garish colours." It is an atmosphere he sums up as "lead, lead, lead," since "from morning to night you do not hear anything else spoken about, nor see anything else, other than lead." This is Spain’s own Black Country, the lead mining areas of Linares and La Carolina in Jaén province.

Mine at La Carolina

The lead is in the form of galena in a matrix of quartz and sometimes barites. The veins are substantial, up to one metre thick, and it is not unusual to find solid masses of galena with no matrix. They were formed by the action of mineralised hydrothermal vents forcing their way through granite back in the Carboniferous period, 350 million years ago. The granite was pushed into the air as a result of the folding induced by the movement of the African tectonic plates into the European plates and eroded to form the sandstone and conglomerate beds above the granite. The beds continued to uplift, fold and fracture and more sedimentary material was laid down until the rolling landscape you see today emerged.

The Romans discovered the lead 2000 years ago and exploited it by digging vertical shafts and horizontal galleries until, in many cases, they reached the water table and then, unlike in the Rio Tinto mines in Huelva, moved on to start another shaft rather than deal with the water. A unique carved relief of Roman miners was found at one of the mines in Linares around 1900 and is now displayed in the museum. Little happened between the Roman period and the modern day. The Spanish and later, British, German and French mining companies found many shafts and spoil heaps, indicating the presence of lead below, but first had to deal with the water. The Spanish employed men to carry bags of water up ladders and along galleries to a central point from where the bags of water were drawn to the surface by a capstan (called a whim in mining jargon), driven by mules. At the Pozo Ancho mine in Linares it is recorded that 192 men carried sacks of water up ladders from a depth of 90 metres to 55 metres. The water bags were then raised to the surface using a whim worked by 24 mules. The British used steam engines and pumps imported from the UK.

Rail track La Carolina

The story of modern mining in Jaén is essentially the story of two families, the Sopwiths (of aeroplane fame in WWI) and the Taylors, a dynastic mining engineering family that hailed from Norfolk, England, and the multifarious companies they registered and dissolved and merged.

In June 1883, the prospectus for the Linares Copper and Lead Mining Company was published in the Cornwall Royal Gazette. It was a landmark announcement because that is the first record that exists of a British mining company coming to Spain. The following year, in September 1844, another announcement in the same periodical confirmed that a steam pumping engine manufactured at Harvey and Co’s factory in Cornwall to the Sim’s patent was on the steamship Trelissick, commanded by Captain Andrews, bound for Seville, on its way to the mine at Linares. The Cornwall Record Office in Truro also has a record of a list of mining equipment bearing the name Linares and the date 1844. The list included miscellaneous items for use in a mine; kibbles and ore washing equipment. An article in the Cornwall Royal Gazette in January 1845 seems to signal the end of the Linares Copper and Lead Mining Company when they announced the death of the mining captain, Joseph Malachy from Devon.

Those first stumbling steps were the precursor to a veritable avalanche of British mining companies into Spain. In 1848, Queen Isabella II of Spain decreed that Spanish and foreign mine operators should have the same rights and protection from reprisals in case of war or its causes. This was followed in 1849 by a second decree that reduced the import duties on machinery, including steam engines and other mining machinery.

Mine in Linares

The Scotsman, Duncan Shaw, who we first met at the failing Guadalcanal mine in Seville province, arrived in Jaén province and obtained the concession for the Pozo Ancho mine. Unfortunately for Shaw, his business partners consisted of ‘booksellers, engravers, solicitors and gentlemen’, not a miner amongst them, so they had to hire a Cornish mine manager. He realized the mine would need capital investment for pumping equipment and Shaw approached the mining consultants, John Taylor and Sons who had a reputation for consolidating groups of mines and bringing them into profit.

John Taylor and Duncan Shaw set up the Linares Lead Mining Association (Linares Lead Mining Company), registered in London in 1851, to raise the necessary capital. Between June 1852 and March 1853, the share price of the Linares Lead Mining Company rose from £3 to £15.

Shaft head gear Linares

Meanwhile, another problem had raised its head; transportation. The Linares Lead Mining Company had decided to export the ore to London rather than receive lower prices from the smelters at Linares and the mine was so rich that it produced more ore than they could handle and store on the surface.

The only feasible route to a port was by a poor road, via Córdoba, to Seville, 250 kilometres of unpaved track, part of which became impassable during winter. All the mining equipment had been brought in that way by donkey and ox cart and the company decided to use that route for outgoing ore. A donkey can carry 0.1 tons of ore, 30 kilometres per day whilst an oxcart can carry 0.8 tons for 11 kilometres per day. The maths says use the oxcart but the company decided to use donkeys for speed. A route to Málaga (same distance, worse roads) was explored and the company even built an ore storage facility at Bailén before deciding to stick with Seville. It sometimes took up to nine months between mining the ore and being paid for it, creating a huge cash flow problem.

The Linares bas-relief. Image: Asociación Colectivo Proyecto Arrayanes.

In 1853, having established the Pozo Ancho mine with two beam engines to extract the water at lower levels and a works programme that involved deepening the mine, a dressing floor and a lead smelter, John Taylor and Sons registered a second company in 1855, La Fortuna Ltd. to explore the nearby Fortuna concession. The company brought in more steam engines. A smelter was also built at La Fortuna. The smelters at Pozo Ancho and La Fortuna solved the problem of selling their ore at a reduced price to the smelters at Linares and reduced the weight and bulk of cargo being taken down the road to Seville.

Fuel for the boilers to run the steam engines now became a problem. Brushwood was almost as efficient as coal but brushwood could not be cut during the summer and most of the brushwood around Linares had already been used. Coal was the obvious and better, alternative, and the nearest place to find it was at Espiel (brought there from the huge coalfields at Belmez), 50 kilometres north of Córdoba. Better quality coal from the UK could also be brought in by ship to Seville and transported to Linares. So, the donkeys carried lead to Seville and returned to Linares with coal and the ships carried lead to the UK and returned to Seville with coal. Duncan Shaw was put in charge of a lead ingot and coal storage facility at Córdoba. There were initially stalls for 60 mules which gives some idea of the extent of mule traffic on the roads.

It was from there that Duncan experimented with different ways of transporting the lead ingots to Seville. His most eccentric scheme, put into operation between 1852 and 1853, was to put the ingots into boxes and float them down the Rio Guadalquivir to Posadas, 30 kilometres west of Córdoba. They would then be transported 70 kilometres by road to Tocina and the final 45 kilometres to Seville by barge.

Movement of people, supplies, machinery, fuel and cargo was by donkey, mule or oxcart along unpaved roads that were impassable in wet weather. The coming of the railway made communications that much more efficient. The railway line between Seville and Córdoba was completed in 1859 and the tramway to the coalfields of Espiel and Belmez opened in 1873.

In 1856 the Linares Lead Mining Association became the Linares Lead Mining Company Ltd. to conform to new company legislation in the UK.

After 1859 the Linares Lead Mining Company moved its smelting operations to Córdoba, near the junction of the tramway and rail line, thereby saving on transport costs of coal and lead. The first smelter at Córdoba consisted of two reverberatory furnaces. Duncan Shaw now found himself in charge of the smelting plant. The company also built a small English cemetery nearby.

The success of the Linares Lead Mining Company attracted others to the area. The Las Infantas Lead Mining Company Limited (1853 to 1855) and the New Linares Mining and Smelting Company Limited (1853 to 1855) were not particularly successful but the San Roque Mining and Smelting Company Limited that showed up sometime later in 1859 lasted eight years until 1867. An early arrival, attracted by tales of rich pickings, was the Anglo-French company registered in Paris, the San Fernando Silver-Lead Mining and Smelting Company who arrived in Linares in 1854. They amused the mining community for twelve months with exaggerated tales of rich veins and motherloads before disappearing quietly in 1855.

La Fortuna Ltd and Linares Lead Mining Company Ltd steadily improved their profits and were paying shareholders two or three dividends per year. In 1862, John Taylor and Sons formed a third company, the Alamillos Mining Company Limited and that proved as successful as the first two.

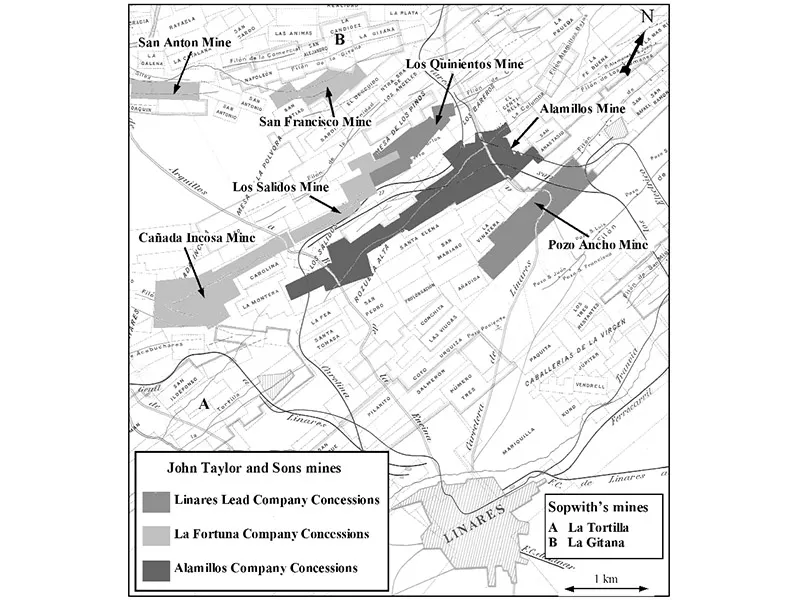

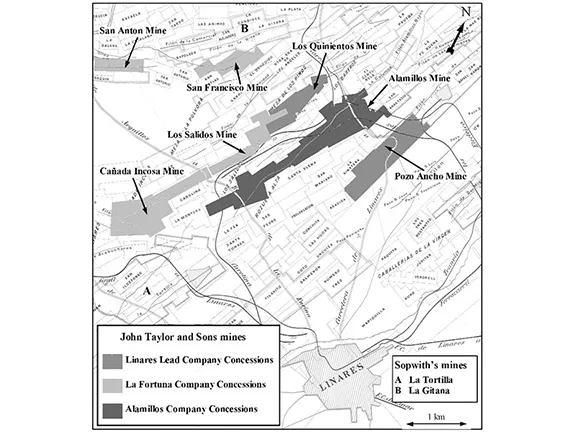

The almost monopoly enjoyed by the Taylors in the Linares area was broken in 1863 when a young Thomas Sopwith junior arrived in town. He had been sent to Andalucia to find potential lead mining prospects by his patron, Wentworth Blackett Beaumont, who controlled lead mines in the north of England. Sopwith identified la Tortilla mine, 2 kilometres west of Linares and, in 1864, a new company, the Spanish Lead Company Limited was registered in London. The first two directors of the company made a formidable team, Thomas Sopwith senior, Beaumont’s mining agent in the UK and Warrington Smythe a renowned mining geologist. They called the first shaft to be explored at la Tortilla, ‘Camel Shaft’, because the previous owner had apparently used a whim driven by camels to bring the ore to the surface. The Sopwiths extended Tortilla mine and acquired the Angustias mine and an interest in La Gitana to the north of Linares.

By 1870, the Linares Lead Mining Company had acquired a group of concessions known as the Quinientos Mine, a mine that was eventually to provide the majority of the output for the company. Throughout their involvement in Linares, the Taylors had the happy knack of being able to open up new shafts and galleries to provide new sources of ore as older galleries and lodes were becoming depleted, thereby maintaining a steady supply of ore to the smelters.

In 1871, Sopwith was appointed the first British Vice-Consul in Linares, a post that was to last until 1948.

Around 1873, Duncan Shaw, last heard of as manager of the Córdoba smelting and storage facilities, made another, brief foray into the mining arena. He tried to establish two companies to work areas to the west of Linares, the Bailen Mining Company Limited in 1873 and the Bailen Company Limited in 1875. Neither company succeeded. The former lasted until 1876 and the latter until 1881.

John Taylor and Sons were not immune to failure. Their fourth venture, Buena Ventura Limited, set up in 1878 to work concessions west of la Gitana, was only moderately successful and closed in 1888.

In 1880, the Sopwiths reformed the Spanish Lead Company Limited to become T. Sopwith and Company Limited. La Tortilla gained a large smelting and lead processing works that was extended in 1885. This smelter had a tower used to produce lead shot. In a shot tower, lead is heated until molten, then dropped through a copper sieve high in the tower. The liquid lead forms tiny spherical balls by surface tension and solidifies as it falls. The partially cooled balls are caught at the floor of the tower in a water-filled basin. The shot tower still dominates the site today.

John Taylor and Sons were also steadily increasing their holdings, working the Majada Honda mine to the north of the mining area, between 1881 and 1883.

The next decade is a period of gradual growth for both mining families. However, towards the end of the 1890s, ore reserves were diminishing as the mines got deeper. In addition, lead prices were reducing due to a flood of cheap Australian lead hitting the market.

The beginning of the 20th century saw both the Taylors and Sopwiths reforming companies and diversifying into other mining areas. The Taylors in particular, invested in new modern equipment such as compressed air drills and double skip-winding systems and, in 1900 even formed another company, Spanish Mining Properties Limited to work a group of mines near La Carolina but output never reached the pre 1890 levels. They were joined at Centenillo, near La Carolina, by another British mining family, the Haseldens.

Meanwhile, the Sopwiths were not faring any better and opened up new concessions at El Fin, west of La Tortilla, to no avail. La Tortilla stopped working in 1903.

When the end came it was pretty quick. Spanish Mining Properties Limited was dissolved in 1903, La Fortuna went into administration in 1914, T. Sopwith and Company Ltd. was dissolved in the same year and finally the Linares Lead Mining Company Ltd managed to struggle on to 1917.

Linares and the mining area surrounding it has been designated a Cultural Heritage Site. The British influence in the town is still highly visible. The English cemetery is a lasting memorial. It was consecrated by the Bishop of Gibraltar in1866. Linares was declared a Chaplaincy in 1872 and administered by clergymen from Málaga. The Taylors and Sopwiths jointly paid for doctors from 1853 through to 1909. The mining concessions in the countryside around the town are studded with mine workings; engine houses for Cornish-style pumping engines, chimneys, shaft head gear, ore dressing floors and smelters. It is all very reminiscent of mining landscapes in Cornwall and is unique in Spain. In the town there is a mining interpretation centre and a museum in the old Madrid railway station and a mining visitors centre at La Tortilla mine.

The landscape around La Carolina is the opposite of Linaris’s undulating fields. The rocks at La Carolina are mainly schists and quartzites and the landscape is mountainous, with deep valleys. One consequence of this is that mine drainage at La Carolina was largely achieved by using adits rather than pumping engines.

In the La Carolina area, British companies established a significant presence at El Centenillo, where Cornish type engine houses still survive but the area was also exploited by Spanish mining companies who were quick to adopt steam technology. The Arrayanes mine for example, managed by the Spanish Government purchased three pumping engines from the Williams' Perran Foundry, Cornwall.

The French also invested in the La Carolina area. La Cruz Company established a settlement, and large smelt works to the north of the town, parts of which still survive, that includes a shot tower partly constructed in a shaft. Further to the northeast the Spanish-French Sociedad Escombreras Bleyberg Company worked the Coto de la Luz mine, and erected a large bull engine on the San Pascual shaft. The engine, boiler house, and chimney survive and provide the sole example of this type of facility where the pumping beam was mounted over the shaft, directly below the steam cylinder.

In addition to the distinct forms of housing used for pumping engines, the area is dotted with those used for winding engines, and ore dressing machinery. Head frames also abound, many constructed from stone. Metal headframes such as the one reconstructed on a traffic island in Linares, are mainly associated with the later phases of mining in the 20th century.

The railway line from La Carolina to Linares was only opened in 1909, too late to rescue the fortunes of the mines.

In the centre of La Carolina the very modern Centro de Interpretación de la Historia de la Minería en las Nuevas Poblaciones de Jaén. the Interpretation Centre for the History of Mining in the new towns of Jaén, provides a detailed history of mining in the Linares – La Carolina area from the Argar people of the Bronze Age through to the last mining venture in the 1990s.

This is a list of the British registered mining companies that came and went in Jaén province. Some prospered, some never got started. There may well be others missing from the list. I have only included those for which there is conclusive information.

Readers should also note that there is little mention of other foreign influence. The French, German and Belgians were also actively involved in mining and providing the mining infrastructure such as railroads and mining machinery, all areas for future research.

Alamillos Co Ltd . Registered: 1862 Dissolved: 1904 John Taylor Company

Alamillos Co Ltd Registered: 1904 Dissolved:1908 John Taylor Company - restructured

Alamillos Co Ltd Registered: 1907 Dissolved:1910 John Taylor Company - restructured

Andalusian Silver Mining Company Ltd. Registered: 1887 Dissolved: 1892 - Worked La Carolina

Andalusian Silver Mining Company, Ltd.Registered: 1892 Dissolved: 1896 Re-formed company

Bailen Company, Ltd. (The) Registered: 1875 Dissolved: 1881

Bailen Mining Company, Ltd.Registered: 1873 Dissolved: 1876

Berenguela Silver Lead Mines Ltd. Registered: 1911 Dissolved: 1921

Buena Ventura Company, Ltd. Registered: 1878 Dissolved: 1890 A John Taylor and Son Company

Cambil Iron Mines Syndicate, Ltd. Registered: 1907 Iron Mines

Centenillo Silver Lead Mines Company, Ltd. Registered: 1886 Centenillo lead mines

Diana Mine, Ltd. Registered: 1913 Worked La Carolina / Santa Elena

Fortuna Co Registered: 1854 Dissolved:1903

Fortuna Co Registered: 1901 Dissolved: 1917

Fortuna Company Registered: 1855 to Co 524

Gitana Lead Mining and Smelting Company, Ltd. Registered: 1871

Heredia Lead Mines, Ltd. Registered: 1902 Agreement with the Spanish Lead Syndicate to buy mines.

Inglesa Mines, Ltd. (La) Registered: 1898 Dissolved: 1903 Record destroyed

Inglesita Mines, Ltd. (La) Registered: Dissolved: 1896 1898 Inglesa Mine Worked La Carolina

La Gitana Mining Company,Ltd (Sopwith) Registered: 1876

Las Infantas Lead Mining Company, Registered: 1853 Dissolved: 1856+

Linares Lead Mining Association Registered: 1851 Dissolved: 1907

Linares Lead Mining Co Ltd. Registered: 1863 to Co 2049

Linares Lead Mining Co Ltd. Registered: 1906 Dissolved: 1917

Linares Mining Syndicate Ltd Not listed Revista Minera RV 1902 Probably replaced the Spanish Lead Syndicate -- San Fernando Mine at La Carolina

Morenilla Linares, Ltd. Registered: 1901 Dissolved: 1912 Las Prolongas group.

Linares Railway Construction Company, Ltd. Registered: 1871

New Centenillo Silver Lead Mines Company, Ltd. (The) Registered: 1898 Worked La Carolina

New Linares Mining and Smelting Company, Registered: 1853 Dissolved: 1853+

San Roque Mining and Smelting Company Limited Registered: 1859

San Roque Mining and Smelting Company, Ltd. Registered: 1859 Dissolved: 1866

Sierra Morena Mining Company Ltd. Registered: 1885 Dissolved: 1889 Worked La Carolina

Sierra Morena Tin Company, Ltd. Registered: 1882 Dissolved: 1906 Desconfianza, Tercera and Carmencita tin mines, La Carolina.

Societe des Anciens Establissments Sopwith Jaen Linares Paris 1907

Sopwith and Company, Ltd. Registered: 1903

Spanish Lead Company, Ltd. (Sopwith) Registered: 1864 Dissolved:1880

Spanish Lead Syndicate, Ltd. Registered: 1902 Interested in the Heredia Lead Mines (San Fernando Mine at La Carolina?)

Spanish Mining Properties, Ltd. Registered: 1900 1903 Worked La Carolina

T. Sopwith and Company Ltd. Registered: 1880 Dissolved: 1914

Vilches Mines Ltd. Registered: 1902 Dissolved: 1911 Worked Linares

References and further reading

Oliva, Pedro Rodriquez. The relief of the miners of Linares (Jaén) from the Deutsches (Bergbau) Museum in Bochum. ISSN 0212-078X, Nº. 23, 2001 (Issue dedicated to: Municipal laws in Hispania: 150th anniversary of the discovery of Lex Flavia Malacitana), pp. 197-206

Rose, H.J. Viaje a la Andalucía inexplorada. Bosquejos sobre la vida y el carácter de los españoles del interior

Vernon, Robert. (2003). Beyond Huelva: Other British Mining Legacies in Andalucia, Spain.

Vernon, Robert. (2006). British archival information relating to mining operations in Spain and Portugal. An overview with examples from Andalucia.

Vernon, Robert. (2009). The Linares Lead Mining District: The English Connection. De Re Metallica. SEDPGYM, (Madrid, Spain). 13. 1 to 10.

Vernon, Robert. (2016). English miners in Spain during the 19th century - Mineros ingleses en España durante el siglo 19.

Vernon, Robert. (2017). Database of British Registered Mining Companies formed to acquire, and work mines, in Spain and Portugal.

Vernon, Robert. (2018). The Linares-La Carolina lead mining field: The publicising, and the conservation of a significant mining landscape in Spain.