First mentioned by the ancient Greeks, then the Romans and even the Bible, the Tartessians are still regarded as a mythical civilisation by many people.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 15 May 2023 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Tartessian Busts from Turuñuelo

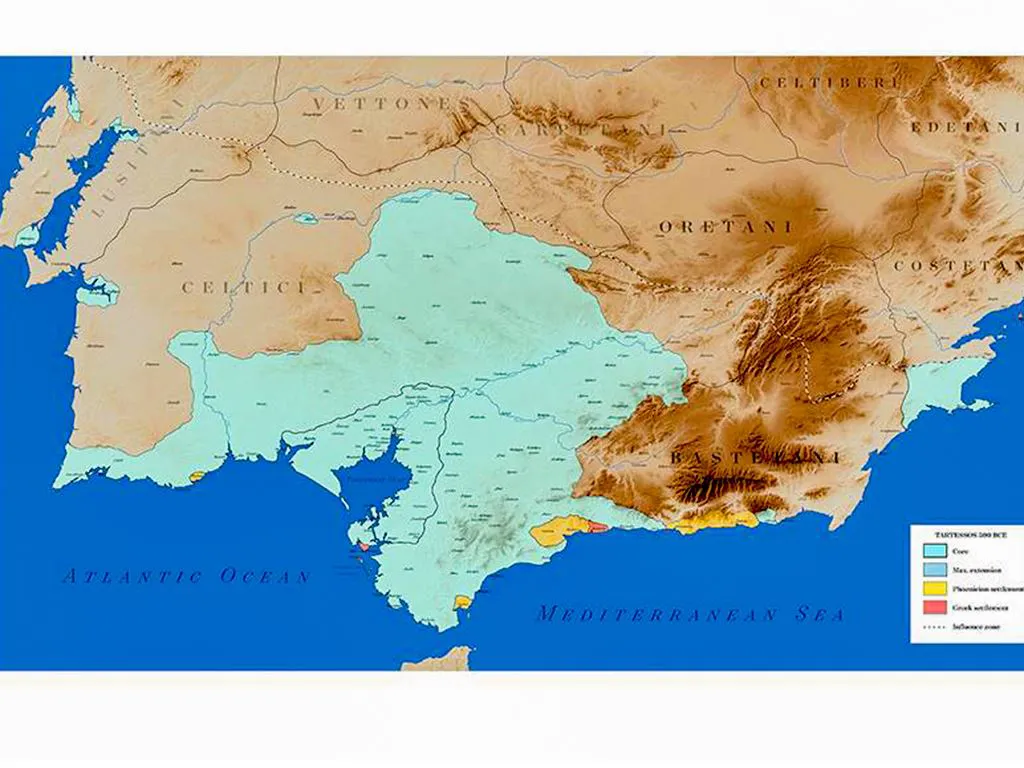

Conventionally the Tartessians were a fabulously wealthy people who inhabited an area in southwest Andalucia in the estuaries and valleys of the Rio Guadalquivir and Rio Guadiana and extended north into Extremadura. Their territory centred in the vicinity of Huelva where they had a city, Tartessos. Their wealth came from trading metals and metallic ores with the Phoenicians from whom the Tartessians gained knowledge of cupellation and methods of extracting iron from iron ore. The Tartessians were the archetypal example of ‘orientalising’ as applied to the Iberian Peninsula, quickly adopting the building styles, art, pottery, fashion and lifestyle of these traders from the east and seemingly welcoming them into their existing communities. Here we extract the facts from the fiction.

Archaeologically the Tartessians seem to have emerged in the 9th century BC only to finally disappear in the 4th. We know of only one ruler, King Argathonius. A language identified on stelae found in the western parts of the Iberian Peninsula has been named Tartessian although only three of the 100 or so examples of the script have been found in the area traditionally occupied by the Tartessians.

When the Romans arrived two hundred years after the Tartessian society had gone, they identified the tribes living in the territory considered to be that of Tartessos as Turduli or Turdetanni, differentiated from other tribes, such as the Iberians to the northeast, by their language.

The Greek historian Herodotus (c 484 - c 425BC) rarely mentions the names of such lowly people as merchants. However, he does make an exception with a Samian (from the Greek island of Samos) silver merchant called Colaeus and Sostratus the Aeginetan (from the Aegean) (Hdt 4.152). Herodotus relates how Colaeus, on a voyage to Egypt, is blown off course by a great storm and finds himself driven into the Atlantic through the Gibraltar Strait. He lands at Tartessus in south western Spain where he obtains a cargo of metal that he brought back to Samos. Colaeus subsequently donated one tenth of the value of his cargo to the goddess Hera. According to Herodotus Colaeus reported that he was the first trader to find Tartessus. Herodotus then goes on to say (Hdt 1.163) that Phoceans (people from an area of central Greece) discovered Iberia and Tartessos and that Colaeus was met by the Tartessian king, Argathonius. This event occurred about 550BC and Herodotus also informs us that Argathonius was killed at the battle of Alalia c 545BC. Just why Argathonius found himself off the coast of Corsica in aPhocaean pentekonter is not recorded.

The name Argathonius is an obvious reference to silver the Greek for which is arguros and the Latin argentum. The Tartessian language is considered by some to have been a Celtic language or alternatively a non-Indo-European language with borrowings from Celtic and Indo European. The Indo-European language had a very similar word for silver, arganto. Latin, Greek, Celtic and therefore Tartessian languages have a common root in the Indo-European language. It is therefore possible that Argathonius is an almost literal translation of the Tartessian name and that at the time of Colaeus the leader of the Tartessians was already a rich man through trade in silver.

Another Greek historian, Ephorus (c 400 - c 330BC) records that the Tartessians were rich in metal, that they had 'a very prosperous market called Tartessos with much tin carried by river, as well as gold and copper from Celtic lands.' Ephorius wrote a 29 volume work called the 'Universal History' covering the period from the origin of the Greeks, the mythical time of the Heracleidae, to the taking of Perinthus by Philip of Macedon in 340BC, a time generally calculated as about 700 years. Unfortunately, he did not write a chronological account of history, it was a themed account.

The next mention is by a Greek geographer and explorer, Pytheas (c 350 - c 285BC) an account later repeated by Strabo in the 1st century AD. Pytheas had departed the Greek emporium of Marsalia to find the source of their trade goods in about 325BC. He recorded that the Turduli occupied the area that was Tartessos which was in the region of the Baetis river (Rio Guadalquivar). Pytheas was the first known scientific observer of the Arctic polar ice, the midnight sun, various Germanic tribes and the first to suggest that the moon had an influence on the tides. His account should be given some credence. Notice he mentions Tartessos in the past tense and the Turduli in the present.

Strabo (63BC - c 24AD) mentions that the lead or stone anchors of ships departing Tartessos were replaced with ones made from silver (Geographica 3.2.8) and Diodorus, a Greek historian writing between 60 and 30 BC, further states that the Phoenicians had to cut down all the trees in the Sierra Morena to gather enough wood to heat the fires of the melting ovens. As far as I am aware Diodorus is the first to mention the Phoenicians in connection with the Tartessians. There is some evidence from Greenland ice cores to suggest that during the period the Tartesians occupied Andalucia, the woodland in the vicinity of Málaga (nowhere near the Sierra Morena) was indeed decimated. Between 900 BC and 600 BC, the population of Portuguese oaks dropped from 15% to 1.2%.

Even the Bible has a possible mention of Tartessos. In Ezakiel 27.12, 'Tarshish did business with you because of your great wealth of every kind; silver, iron, tin, and lead they exchanged for your wares'. Ezekiel is thought to have been written between 593 and 565BC which would make it the earliest reference to the Tartessians if Tarshish can reliably translate to Tartessos or Tartessians. Unfortunately Ezekiel fails to indicate where Tarshish actually is. It is likely that Ezekial is referring to a joint venture between Solomon and Hiram I of Tyre around 950 BC. Tarshish could be Tartessos, or it could be a town in Turkey called Tarsus, now in Cilicia. It has even been suggested that Tarshish was Carthage (Tunisia).

In January 2023, Eric Anthony identified two more biblical references, Isaiah (23:1) and Jonah (1:3). Jonah intended to flee to Tarshish which the John MacArthur Study Bible connects to Tartessus in Spain, citing Greek historian Heroditus.

Sometimes it is what is not said that is informative. From all these accounts it is interesting that none actually call Tartessos a civilisation, even with the vagaries of translating between ancient languages and modern, in the classical way we think of civilisations, the Babylonian, Hittite, Greek, Egyptian etc. There is no evidence here or elsewhere that the Tartessians were expansionist, or even that they had any form of military, on land or at sea.

Southwest Andalucia had been an area of rapid development ever since the Neolithic people arrived about 5800 BC. The fertile valley of the Rio Guadalquivir and, to a lesser extent, the narrow coastal strip along the Mediterranean coast, together with the wetter climate in the west caused by the prevailing winds off the Atlantic Ocean meeting the west facing highlands of the Sierra Morena, Sierra Grazalema and the Alcornocales, reduced crop failures and encouraged an increase in population, compared to the more arid, eastern parts of Andalucia.

The increase in population had encouraged the formation of family clusters, that became settlements whenever population densities rose above a certain level. This appears to be a phenomenon or urge that is built into the human psyche since it has occurred all over the world at different times, despite there being no possibility of communication between those populations separated geographically and in time.

How the societies developed following the initial clustering depended on the environment, climate and outside influences. In some parts of the world societies have developed to a certain level and then failed, only to be reborn, sometimes on numerous occasions. So it was with the Tartessians.

Soon after the Neolithic period started, people started to claim the land in western Andalucia. From about 4700 BC, they built megalithic structures, symbols on the landscape populated by ancestors, thereby proclaiming their ages long ownership of the land. The megalithic phenomenon expanded from Huelva and Cadiz provinces, up the Guadalquivir valley into Granada and Almeria. The so-called ditched enclosures appeared. These are now thought to have been communal areas demarcated into spaces in which different activities occurred, ceremonial, metalworking, animal butchery as well as in some instances, dwelling spaces. Single burials became multiple burials and, towards the end of the period, regressed back to individual burials, often cremated. The huge site of Valencina de la Concepción at Seville is the most researched site that combines all these features.

Meanwhile, in southwestern parts, copper had been discovered and the methods of producing the metal from the ore, and useful ornaments and tools, had developed. The metal rich Sierra Morena, stretching from Portugal to Murcia and the Baetic mountains from Huelva to Valencia, are rich in minerals and the use of copper spread up the settlements within and adjacent to those mountains.

The archetypical Copper Age site is still that at Los Millares in Almeria province. The copper mines at Rio Tinto in the centre of the Tartessian area, are the oldest mines in Andalucia, surface mining having started about 3000 BC. Silver and gold is also found at the south western end of the mountains whilst lead and iron are more prevalent in the north eastern parts.

At this point the histories of the lush, fertile southwest of Andalucia started to diverge from that of the arid north-eastern parts of Andalucia. In the severe, arid environments in the north-eastern parts of Andalucia, the environment seemed to encourage a strict society. Perhaps this was necessary to keep rigid control of reserve produce. The Los Millares people started to build their settlement soon after 3000 BC. Their settlement declined and disappeared about 1800 BC, to be replaced by the El Argar people, a hierarchical society as harsh as the environment. The El Argar society declined during the 14th century BC and the population dispersed into scattered agrarian settlements and isolated fortified towns. In this area, the north-eastern parts of Andalucia, the next steps towards statehood did not occur until the Iberian society became evident about 700 BC.

At the same time, from 3000 BC until about 900 BC, in the fertile areas attributed to the Tartessian people, settlements continued to expand without any sign of formal control. It was a dispersed agrarian society that did not at first appear to need strict regulation in order to survive and prosper. The larger, walled and sometimes moated towns began to appear in the 8th century BC.

Over millennia, trade and communication networks had become established in the Iberian Peninsula. The southwestern parts of Andalucia were at the southern end of a route that became known as the Atlantic Bronze Trade.

The Atlantic Bronze Trade route linked the northern extremities of Europe with Brittany, Portugal and southern Spain. Finished items such as bronze cauldrons, roasting spits and swords moved along the route along with raw materials such as tin. It became most apparent during the megalithic period, the phenomenon and materials moved along this route, from Portugal, south and east through Andalucia. Andalucia was also fortunate to have links with North Africa. Goods of various kinds moved along the Atlantic network in both directions. The copper and gold from Andalucia (mainly from the southwestern parts), plus exotic items such as ostrich eggs and ivory from Africa guaranteed the Andalucian people a place in the trading ‘club’.

From the 11th century BC, communications east into the Mediterranean were re-established after a thousand year hiatus. A few objects originating in the eastern Mediterranean started to appear in the Iberian Peninsula and Huelva type fibula and an Atlantic rotary spit were found in a 10th century BC tomb in Cyprus. Fibula have also been found at different places in the Levant, all in 10th century contexts. Bronze items from Iberia, such as swords, axes and adzes have also been found in Sicily.

Tartessian Territory 500 BC

In the 9th century BC, the Phoenicians established a trading post on the Atlantic coast at Gadir (Cadiz). They had probably been making seasonal, exploratory visits to the coast for a few hundred years prior to them deciding they needed a trading colony. The 11th century resumption of trade between the western and eastern Mediterranean could easily have been a sign of those early exploratory visits. The Phoenicians were particularly interested in the metals from the southwest as well as the agricultural produce, timber, fish and salt. Their arrival acted as a catalyst in the southwestern parts of Andalucia. They not only introduced new ideas and techniques; they developed a huge market in the eastern Mediterranean for products from Andalucia.

The arrival of the Phoenicians gave a huge boost to the Tartessian society. Having established Gadir the Phoenicians then worked backwards, establishing trading posts along the Mediterranean coast. These trading posts were inhabited by the local population as well as by Phoenicians. The local inhabitants providing the link with settlements inland and the manpower to grow the crops, work the fish salting factories, harvest the salt, cut the trees and mine the ores. They would soon be adopting new metal working and pottery manufacturing techniques and manufacturing finished products that became part of the portfolio of goods traded by the Phoenicians.

Because the Phoenicians decided to prioritise the western part of Andalucia, the people who inhabited that area, the Tartessians, benefitted from being the first people to be introduced, not only to the eastern Mediterranean markets, but new ideas and techniques from the east. The proliferation of Phoenician settlements back east along the Mediterranean coast explains why it was that some two hundred years elapsed before the tribes in the Iberian area started to become orientalised - a word used to describe the adoption by local people of eastern Mediterranean habits, customs, technology, dress and architecture.

The Tartessian advantage was compounded by another series of events that occurred in the far north-eastern parts of the Iberian Peninsula and later in the north and central parts; the migration into the country of Celtic tribes in two waves, in or around 900 BC and between 700 and 600 BC. These initial migrations had an impact on the Iberian tribes and the tribes in the central meseta, but none, or little, on the Tartessians. However, the final demise of the Tartessian society between the 6th and 4th centuries BC may have been as a result of increasing pressure from the Celtic tribes to the north on their final pieces of territory in Extremadura.

It is a mistake to totally separate the Tartessian society from the Iberian society that developed in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula and whose territory extended from Málaga well into southern France. Effectively they were from the same stock but developed in slightly different ways despite them being neighbours. No doubt there was a degree of ‘blurring of cultures’ at the boundaries between the two tribes. As it transpired the Tartessian society developed from the 10th century BC, the Iberians from the 8th century BC. The Tartessians declined after the 6th century BC whilst the Iberians, with a more robust system of government, continued until the Romans arrived in the 3rd century BC.

Bronze Urn from La Joya

Unlike the Iberian societies to the northeast, the Tartessian society was not initially, apparently, based on a strictly hierarchical structure. Its agrarian economy in each community was robust enough not to need the administrative overheads required to regulate the storage and supply of grain and other food stuff, imposed by the Iberians. The Tartessian chiefs gained their authority from the exotic and luxurious goods from, at first northern Europe and then, after the 10th century BC, the eastern Mediterranean. Their wealth came, not from surplus grain and livestock, but from the accumulation of foreign products and control of the metal production industry. Hence the stories of accumulations of fabulous wealth in the form of silver and gold.

When the Phoenicians established Cadir, there was already a well-established trading society that they simply plugged into. The indigenous people continued to control the mines and provide food, manpower and wood and they also controlled the manufacturing processes, not only of metals and the items made from them, but also pottery, including amphorae to carry the ‘exports’.

The Tartessians were not slow to produce other products valued by the Phoenicians such as the purple dye made from the shell of the murex sea snail, garum, a preserve made from rotting fish entrails, and salted fish. A whole new type of society was created based on the acquisition, manufacture and redistribution of goods, a true consumerist society. The members of the different dynasties started to have themselves entombed in impressive grave mounds. Initially the mounds were used to inter one person and were then used repeatedly for more burials. DNA analysis of bones excavated from a few of the mounds show that each of the mounds belonged to a single family.

A handful of these tombs stand out for the quantity and value of the grave goods and the amount of labour that went into building the mound. The best example to date is probably the Huelva necropolis tumuli of La Joya. This tumulus is huge and dates to the 7th century BC. One individual is interred in the stone chamber. He was accompanied by two iron knives with ivory handles, a rare bronze thymaterion (an incense burner used in religious and spiritual contexts) and a bronze, two wheeled chariot in a style seen in the Middle East.

The Carambola Hoard

Whilst the La Joya chariot could not have been used in practice and was of ornamental value only, so could be described as ‘art’, the Tartessians are best known for their artistry in jewellery. The finest examples were found in the sanctuary at El Carambolo (Carnas, Seville). The Tartessian sophisticated craftsmanship is illuminated by a magnificent set containing 21 different adornments, including two bracelets, seven necklaces and 21 rectangular plaques made of gold. This set, weighing a total of 2.39 kg, was found buried in an urn. The ensemble dates from the early 7th century BCE. The beautiful 24 carat golden pectorals from that hoard show a unique mix of oriental motives and Atlantic techniques and technologies. The ‘lost-wax casting’ technique, which uses a wax model to duplicate the object in metal form, was a refined method of casting bronze used in the British Isles at that time. The technique can be found executed in different pieces of the hoard. The hoard is believed to have belonged to a group of priests who used the objects in their ceremonies in the sanctuary.

The Phoenicians brought with them the potter’s wheel. By the 9th century BC, Tartessian potters were turning out unique and beautiful hybrid ceramics, imitating the oriental ware favoured by Phoenicians. There are examples of hand moulded ceramics in the shape of Phoenician jugs with painted decoration of solely Iberian patterns, merging the two cultures and leading to speculation that the Phoenicians physically occupied at least the coastal areas.

Of more interest to the Phoenicians were the metals from the Sierras. To this end they introduced the processes of cupellation and casting. Cupellation is a process by which impure gold or silver is melted in a flat, porous dish, a cupel, that then has hot air blasted over it in a special furnace. The result is a pure form of the metal and a slag.

Model of Cancho Roano

Early Tartessian villages were identical to the Bronze Age settlements before them, circular or rectangular dwellings set on a stone plinth. Walls were stone or adobe with a roof made from beams and thatch. The single living space would have a central hearth and a cobbled entrance. There was no urban planning.

In some areas the Tartessians built so called 'pit houses' that were partially dug into the earth. When these were abandoned, they were usually filled with rubbish. There is some dispute that these pits were ever dwellings.

Castillo de Doña Blanca

Castillo de Doña Blanca is built on an elevation near El Puerto de Santa Maria, and was occupied for long enough for a tell to develop. Three thousand years ago, the Bay of Cadiz extended much further inland than it does today and Castillo de Doña Blanca was a port throughout the Punic period, associated with Gadir on its island, at the mouth of the bay. Occupied between the 8th and 3rd centuries BC it has been argued that Castillo de Doña Blanca was a true Phoenician town with most of the occupants being Phoenician. A wall of typical Phoenician design surrounds the settlement.

Castillo de Doña Blanca was originally occupied by indigenous people from about 2000 BC, the site was abandoned about 1500 BC and then re-occupied about 750 BC. Castillo de Doña Blanca contains one of the oldest wineries in the world.

The 8th century buildings are generally covered by a layer of sediments accumulated from later times to a depth of 7 to 9 metres. However, a large area has been discovered, outside the archaic city, in which there have been no subsequent building, which has allowed the excavation of a large sector of houses belonging to those times. The houses are arranged on artificial terraces, that take advantage of the natural slope of the land. They are composed of 3 or 4 quadrangular rooms, built with masonry plinth foundations and adobe walls, plastered with clay and lime. The floors are made of rammed red clay and the roof is flat or one-sided, made up of wooden beams and a roof composed of turf. Most of the houses had a bread oven consisting of a domed clay structure approximately 1 metre in diameter at the base.

During the 8th century BC, the town was provided with a wall, a small part of which is visible today. It rises directly from the natural terrain and is built of irregular masonry interlocked with red clay; in the excavated areas a height of 3 metres is preserved. Just in front of the wall was a moat, with a V-section, 20 metres wide and 4 metres deep. This wall and moat were in use until the 6th century BC at which time a new wall was built that only partially reused the previous one. Finally, between the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, the last fortified enclosure was built. The latter wall was built after the demise of the Tartessians so it could well be a Carthaginian construction.

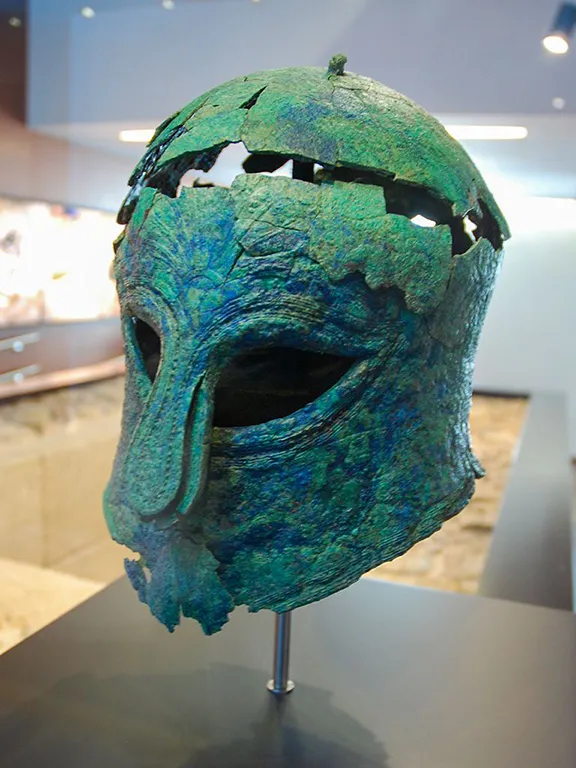

Corinthian Helmet at Jerez

The Tartessian village at Acinipo, near Ronda in Málaga province is a good example of a Tartessian village with round dwellings with cobbled entrances. Acinipo was on the eastern edge of the Tartessian territory, abutting the Iberian territory. It was later occupied by the Romans.

Corinthian Helmet at Malaga

Larger settlements were built on elevated positions. External walls started to appear during the late 9th, early 8th century BC. These tended to be parallel stone walls stuffed with earth and sand. The Cabezos de San Pedro is a hill located in the centre of Huelva city. It has been identified as a Tartessian settlement dating to the 9th century BC. The wall is built as described, which is a recognised technique originating in the Levant.

The earliest built walls of Carmona in Seville province are similar to those at Cabezos de San Pedro but, the most impressive build dating from this early Tartessian period is that of the 22 hectare site in Manilva municipality, Málaga province, Castillejos de Alcorrín.

The walls that surrounded the site at Castillejos de Alcorrín, were 4.3 metres thick punctuated with circular turrets. Buildings within were rectangular separated by streets. Some researchers have suggested it could have been a fortress solely for the use of the local chiefs who controlled the area. Pottery has been found within the walls with Phoenician script. Analysis of the ceramics show they were made at Málaga. Castillejos de Alcorrín, dating to the 9th century BC, is notable for being one of the earliest Tartessian sites to be found.

Archaeologists have so far identified a number of settlements that had protective walls with strong stone foundations that have been interpreted as major trading centres during the Tartessian period and these include: Niebla (Huelva province), Cabezo del Castillo de Aznalcóllar and Carmona (Seville province), and Ategua (Córdoba province), along with Los Castillejos de Alcorrín (Manilva, Málaga), and Castro de Ratinhos (Moura, Portugal).

Between 586 and 573 BC, the Phoenician city states in the Levant were being threatened by Nebuchadnezzar II, the king of Babylon. Eventually, in 539 BC, the Phoenicians lost their homeland to the Persians. This led to a reduction in the demand for, or at least a reduction in the trade of, products from the western Mediterranean to the eastern Mediterranean. The mines of the Rio Tinto were closed, and related industries declined during this period. The settlements surrounding the ‘Tartessian Gulf’ (an extended Bay of Cadiz), were abandoned. Some had only been in existence for 50 years.

At the same time as the Persians were causing stress amongst the Phoenician traders, more Greek products were appearing in the Tartessian territory. This could have been caused by the Iberian tribes that had developed after 700 BC, pushing southwest from their homelands in the northeast of Andalucia. At the same time, after 650 BC, the Carthaginians were expanding their influence and took over many of the Phoenician coastal settlements such as that at Carteia (San Roque, Cadiz) and Malaka (Málaga), imposing their own magistrates and administration.

The Tartessian society started to decline during the 6th century BC. Some of the typical Phoenician trade was taken up by Greek products as evidenced by the Corinthian helmets and armaments found in the province. A bronze helmet was discovered whilst dredging the river at Huelva. It was manufactured by Greeks in southern Italy and is dated to the latter half of the 6th century BC (550 – 500 BC).

A second helmet was found on the west bank of the mouth of the river Guadalete at a place called La Cora. This helmet is thought to have been manufactured in Greece and dates to the beginning of the 7th century (700 – 675 BC). It is displayed at the museum at Jerez de la Frontera.

A third helmet was found at Sanlucar de Barrameda at the mouth of the Rio Guadalquivir. This one was dated to the middle of the 6th century (about 550 BC). This helmet is in a private collection.

The fourth helmet is on display at the Málaga Archaeological Museum. It was found at Málaga and dates to around 650 BC. This latter helmet was found in a burial context, the human remains being in a cist. Grave goods included the helmet, some spear points and possibly a shield.

A cuirass, or breast plate of the Greek ‘muscle’ type, was found off the coast of Almuñecar in 1967 associated with amphorae and presumed to be the remains of a shipwreck. The cuirass has been tentatively dated to the 6th century BC.

Other Greek items found tend to concentrate in the southwest of the province. At the Tartessian necropolis of Bencarron (Seville) an ivory casket depicting a kneeling warrior facing a lion has been dated to between the 700 and 600 BC. A clay disk from Cerro del Villar (Málaga) dated to the 6th century BC depicts a Greek warrior. Shards of Greek pottery have been found as far away as Cabezo de Alcalá in Aragón, proof of the trading network in operation at this time.

It is possible that the Greek products were picked up by the Phoenicians in the Greek trading post of Empúries (Ampurias) in Catalonia rather than brought directly in Greek trading vessels.

Even the Greek influence ceased after 535 BC as a result of the Persian invasion of Ionia and the Pyrrhic victory of the Phokaians at the Battle of Alalia.

The net result was that the Tartessian elite could no longer sustain their newly formed hierarchy and the Tartessian communities could not handle the waning of their economy’s most influential trading partners. In the eastern parts of its territory, adjoining that of the Iberians, the Tartessian society started to revert to a dispersed agrarian people, similar to that which had existed before the Phoenicians arrived.

The return to the land spread west and north through what is now Andalucia and the final, at least to date, redoubts of Tartessian society are to be found at Cancho Roano, La Mata in Campanario and Turuñuelo, all in Extremadura.

Cancho Roana dates from 550 BC. The main body of the building is square and oriented toward the east. The building is surrounded by a deep moat, which was permanently filled with water. Although Cancho Roano's exact function is unknown, the religious character of the site is undeniable due to the presence of altars; however, the site may be a palace-shrine, judging from its defensive system. It was destroyed, probably deliberately, by fire in 370 BC and the building sealed with rammed earth.

Turuñuelo was only discovered in 2015. Early indications are that it is greater in extent than Cancho Roana, although only about 10% of the one hectare site has been excavated. In the ruins of a palace/shrine were found the sacrificed remains of 22 horses, three cows, two pigs, two sheep and one donkey. Other remains include sacks of grain, goblets, weighing scales and bronze items. As with Cancho Roana the whole building was burned and buried at the end of the 5th century BC.

La Mata has been interpreted as an administrative centre. It was a dwelling protected by two towers and a perimeter wall with a surrounding moat. Nearby is a necropolis. La Moya was destroyed by fire and buried about the same time as Cancho Roana and Turuñuelo.

There have been no signs of any conflict or weapons found in the abandoned ceremonial sites, towns, villages and settlements. It has been argued that the Tartessian people blamed their gods, rather than their chiefs, for the decline of their society and that, prior to the final abandonment of places like Turuñuelo they had sacrificed animals to their gods in an effort to appease them and possibly indulged in a banquet that would have been organised by the priestly caste or the chiefs. Following the ceremony, the settlements were ritually burnt and buried.

As we now know, it was not the gods that deserted the Tartessian. It was their trading partners that disappeared, taking with them the raison d'etre of the Tartessian elite. The Tartessian governing system depended upon a continuing production of products for export and a continuous supply of foreign imports. As the population grew so the requirement for manufactured goods and imports increased. When that cycle was broken, the society fell apart. The Iberians had a governing system that depended on the production of food and the control and distribution of food reserves, a system that ultimately proved more resilient.

Some sources say that Tartessos was a state. States are defined as ‘a body of people that is politically organised, that occupies a clearly defined territory and a sovereign political system that governs the people in that territory.’

At the moment (2020) there is barely enough evidence to claim that the Tartessians created a state. They almost made it but, unlike their neighbours, the Iberians, they did not quite get there. There is insufficient evidence to show they had a unified political system. This may be because there are not enough examples of Tartessian script to enable that information to be retrieved, or that, because they disappeared before the Romans arrived, their society was never adequately described by the first historians. However, this opinion may change as more research is undertaken.

Until then, I prefer the word society to describe the Tartessian civilisation. A society is defined as, ‘a community, nation, or broad grouping of people having common traditions, institutions, and collective activities and interests.’

From the evidence gathered to date. The Tartessians were an indigenous agrarian people who lived in the southwestern part of the Iberian Peninsula. Over hundreds of years they had established a trading relationship with north Africa and north into Portugal based on their discovery of precious metals in the southwestern part of the Sierra Morena mountains. They became a distinct society as a result of contact with Phoenician traders during the 9th century. The Tartessians could be distinguished from other societies that coalesced at a similar or later time, such as the Iberian society, by a certain lack of centralised government and a dependence on exotic imports to uphold the authority of their elite rather than an authority derived from control of home grown or home produced products. Finally, although a subjective argument, the Tartessians appear to have been more eager devotees of what is now known as orientalising than other societies then existing in the Iberian Peninsula.

Some historians think that the Tartessians were Celts or Ibero-Celtic. From the evidence we have this seems to be very unlikely. Celtic tribes certainly inhabited central and western parts of Spain from the 6th century BC onwards, they may even have been partially responsible for the decline of the Tartessian society, particularly in parts of present day Extremadura but the Celts were not Tartessians. There has also been some debate that the Tartessian language was similar to Celtic based on scripts found in the southwest of Iberia. It has now been determined that southwestern script is the most ancient Paleo-Hispanic script, with characters most closely resembling specific Phoenician letter forms found in inscriptions dated to c. 825 BC.

With little data to go on it is assumed that the Tartessians were polytheistic like many other societies around the Mediterranean. It is probable that they embraced the female Phoenician goddesses, Astarte or Potnia and the male gods Baal or Melkart.

In May 2023, archaeologists from Spain’s National Research Council (CSIS) on Tuesday presented the amazing results of excavations at the Casas de Turuñuelo dig in Badajoz.

Five busts, two of which show great detail, are the first human and facial representations of the Tartessian people that the modern world has ever seen.

The hoop earring jewellery and hairstyles of the busts resemble ancient sculptures from the Middle East and Asia. These “extraordinary findings” represent a “profound paradigm shift” in the interpretation of Tartessian culture, excavation leaders Celestino Pérez and Esther Rodríguez said during a press conference.

The team believe the busts, some 2500 years old, were excavated from a shrine and represent Tartessian goddesses.