The Vikings’ first attack on the coast of Spain was in 844 AD during the reign of King Ramiro I of Asturias

By Nick Nutter | Updated 11 Apr 2023 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

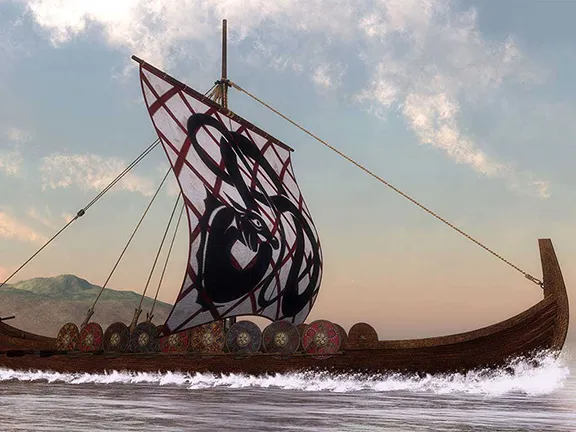

Viking Longship

On the morning of Thursday 25th September 844 AD, the citizens of Isbiliya, better known today as the city of Seville, were horrified to see, emerging ghostlike through the mist over the Rio Guadalquivir, the square, red striped sails of 54 Viking longships. The panicked populace were easy prey for the marauders and the outskirts of the city were sacked by the 1st October. A defending force held out in the Alcazabar, anxiously awaiting relief.

Viking Army reconstruction

It is only in the pre-Franco era that any research, or interest, has been shown in the lesser events of history from this period in Spain. Historians have tended to concentrate on the larger picture. In 844 AD, that was the Muslim occupation of al-Andalus, in particular the Independent Emirate that ruled al-Andalus from their capital at Seville between 756 and 929 AD. Yet the fact of the Viking incursions into the Iberian peninsula is remembered by local folk. Every year, on the first Sunday in August, the replica of an 11th-century Viking longboat sails up the river Ulla to the town of Catoira in northern Spain. The festival commemorates Galicia’s resistance to the Viking raids that took place there more than 1,000 years ago, when the invaders tried to plunder the treasures of the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. Indeed, the Vikings may have left a more permanent reminder of their activities, there are Spanish natives, particularly in the northern regions, with blonde hair and blue eyes.

Viking Longship

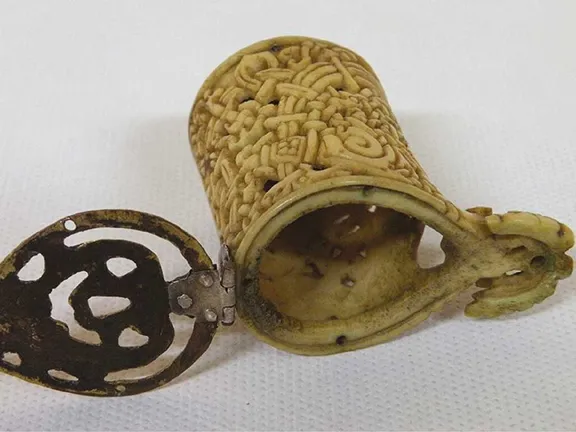

There is very little archaeological evidence of the raids. In 2014 a storm off the Galician coast uncovered four stone, Viking anchors. A couple of mounds that may turn out to be longphorts, or Viking encampments, have been discovered nearby and a cylindrical container found at San Isidoro in León is the only Viking object known from the Iberian Peninsula. The latter could just as easily have been brought to Spain by traders as by Vikings. Interestingly, the assumed longphorts are close to an ancient gold mine and a number of religious settlements, favourite targets for Vikings.

Conversely, only a few coins from the Emirate have been found in Scandinavia and these could easily have been as a result of trade rather than booty from raids.

San Isidoro container

Most of what we know about the Viking raids on the Iberian Peninsula comes from accounts written mainly by Arab historians, who referred to the Scandinavian interlopers as majus, meaning ‘heathen or worshipper of many gods’. Accounts of the Viking raids appeared in the works of Muslim historians, including Ibn al-Qutiyya of Córdoba (d. 977), Ibn Idhari (wrote about 1299, copying 10th century sources) and al-Nuwayri (1284–1332). They are also mentioned in the Chronicle of Alfonso III, composed in the early 10th century and in the Annales Bertiniani, late 11th century, Frankish annals that were found in the Abbey of Saint Bertin, Saint-Omer, France, after which they are named. Then further mention of the raids started to appear in the works of Spanish historians, notably Modesto Lafuente y Zamolloa in the 19th century, although his sources of information are not well known. It is unfortunate that the Vikings themselves were not the greatest diarists in the world so we do not have any contemporary accounts from their side.

The Vikings were a seafaring people from the late eighth to early 11th century who established a name for themselves as traders, explorers and warriors. They discovered the Americas long before Columbus and could be found as far east as the distant reaches of Russia. While these people are often attributed as savages raiding the more civilized nations for treasure and women, the motives and culture of the Viking people are much more diverse. These raiders also facilitated many changes throughout the lands from economics to warfare.

Perhaps the most famous feature of the Vikings, apart from the horned helmets that they never actually wore in battle, is their longships. The Vikings had highly developed boatbuilding skills. These vessels, well known from various ship tumuli are examples of something approaching perfection in Mediaeval boatbuilding. They are extremely seaworthy and could achieve considerable speed employing oars or sail. Their design allowed them to be used in the open seas, close to shore, up rivers and, if necessary, they could be disassembled and carried overland. The Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune ships are all good examples of the Viking longship.

The Viking Age started with a Viking raid on the monks of Lindisfarne, a small island located off the northeast coast of England, and it lasted until the 1050s, a few years before the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. During this time, the reach of the Scandinavian people extended to all corners of northern Europe, and many other nations found Vikings raiding their coasts. The farthest reported records of Vikings were in Baghdad for the trading of goods such as fur, tusks and seal fat.

The Viking strategy seemed to be voyages of exploration, reconnaissance and trading followed by voyages for plunder and finally, voyages to settle land. There is much dispute as to whether settlement involved conquest first or whether the Viking immigrants, mainly farmers and traders, peacefully integrated themselves with native populations. What is known is that the population in the Viking homelands increased sharply at the end of the 8th century, forcing them to look for new land in which to settle. This pressure to find new lands was exacerbated by religious persecution. The Scandinavian Vikings worshipped many gods which the European Christians found abhorrent.

However, the Viking raids into Iberia did not lead to intentional settlement as far as we know, the Vikings that raided al-Andalus had plunder and slaves in mind.

Although news did not travel as fast in the 9th century AD as it does today, it is surprising just how far afield the wealth and opulence of the Independent Emirate in the Iberian Peninsula was known and how that knowledge spread.

Neither the Westfalding, the generic name used by Norsemen for Vikings from the Britannic or Irish Sea, nor the Muslims can have found the campaign in Andalucia as strange as some historians have assumed. More than four decades had passed since the Vikings had first raided the coasts of Aquitaine; Irish monks for two centuries had had some knowledge of the Spanish scene; and it is clear that the Vikings had a general idea about the peninsula before they descended upon it. They found in Seville a population which was still largely Gothic and Hispano-Romano. The Gothic elements were important in the Andalucian Amirate. Musa al-Qasi, who took a leading part in the defeat of the Vikings at Tablada (near Seville), belonged to a powerful Muwalad family of Gothic descent. The Amir’s household troops were composed of non-Arabic speaking troops, partly negroes and partly Slavs. Also, there were in Spain thousands of slaves ímported from the eastern borders of the Frankish empire, many of them taken in the Carolingian wars, Saxons, Slavonic Wends, and, doubtless, Danes. Some of these men had become freemen and had risen to good positions in service or in trade. The Westfalding seem to have had no difficulty in finding interpreters and in making themselves understood. No doubt the truth of the wealth of the Independent Emirate, which was considerable in any case, was greatly exaggerated by the time the stories reached northern Europe via the itinerant traders who travelled all over Europe. Sufficient in any case to motivate the Vikings. Who led the Viking raid is not known. They are presumed to be under the overall command of Björn Ironside the legendary King of Sweden, and Hastein, a Viking chieftain who led a number of raiding parties.

The Vikings’ first attack on the coast of Spain was during the reign of King Ramiro I of Asturias. Part of the Viking fleet approached the Asturian coast in the vicinity of Gijón, but when they realized how strongly this city was fortified, they left. They then arrived at the old lighthouse at Coruña called the Hercules tower, but which at the time was generally known as the Farum Brigantium. They unsuccessfully tried to take the city. Whilst the residents held out against the Vikings, King Ramiro gathered an army in Galicia and Asturias and defeated the Vikings in a fierce battle near the Hercules tower. The battle rates two mentions by Spanish historians, 'This victory', says Florenz, 'must be reckoned among the most glorious in our history because the Vikings were so powerful'. The Spanish historian Lafuente says, 'it is a great honour for the king of the Asturians to have protected his small states against those horrible Vikings, who had planted their seeds of destruction in the midst of great and powerful states.'

The Vikings escaped to their ships, but not before ransacking the countryside and churches for about 15 kilometres inland. They sailed around the Punta Nerija hill west of Coruña and sailed to the south plundering and ravaging as they went. They reached Lisbon and took possession of the city and the plains around it and stayed there for 13 days. Thereafter they sailed to Cádiz and attacked Medina Sidonia before sailing north into the Rio Guadalquivir and thence upriver to Seville where they arrived on the 25 September 844. The city fell on the 1st October after some fierce fighting, and the Vikings stayed there for 40 days.

During their time at Seville, the Vikings ravaged the surrounding area from their encampment on the Isla Menor and sent expeditionary forces out towards Córdoba and Moron. They did not manage to take the Alcazabar, that held out until it was relieved. Out of pique, the Vikings tried to set the mosque on fire but were prevented from doing so. The Muslims put this down to divine intervention.

Emir Abd ar-Rahman II of Córdoba appealed to the other governors and raised an army, led by his chief minister, Isa ibn Shuhayd. The troops gathered at Carmona and included a contingent led by Musa ibn Musa al-Qasi, the leader of the semi-independent Banu Qasi principality to the north, who joined this army despite Musa ibn Musa's political rivalry with Abd ar-Rahma. An example of how competing Muslim forces often allied to defeat a common enemy. The Viking detachment that went towards Moron was ambushed and slaughtered by the Muslims at a place known then as Quintos-Moafir. The Vikings remaining on the Isla Menor, having learnt of the defeat at Quintos, fled the city.

A number of minor skirmishes occurred until, on the 17th November, the Vikings were brought to battle by Isa ibn Shuhayd at Talyata, Italica, just north of Seville. Defeated, the Vikings retreated down the Guadalquivir and back to Cadiz.

One of the reasons the Muslim armies were successful against the Vikings is that the Vikings had to fight on foot. They had no horses, whilst the Muslims had light cavalry.

They did manage to sail up the Rio Tinto to Niebla, famous for its silver mines, and sacked the town. The Vikings then retraced their path, via Beja and Osasunna in Portugal, to Lisbon. From there the trail goes cold and nothing further is heard about this particular raiding party. Almost as a footnote, it is recorded that some of the Vikings stayed behind, having been cut off from the main forces in al-Andalus. They converted to Islam and became, of all things, cheese traders. They took to dairy farming in the valley of the Guadalquivir and for decades supplied Seville and Cordoba with a cheese that became famous in al-Andalus.

As a result of this raid, Abd ar-Rahman established a naval arsenal at Seville. The coastal torres also started to appear, though the main motivation for those was to ward off attacks by other marauders from closer to home, the Barbary pirates. Linked to the towers was a series of messenger networks that warned the local populace of attacks from the sea.

The major defeat suffered by the Vikings in 844, did not prevent them trying again in 859 AD. Once again, the combined Asturian and Galician forces defeated them. In 860 AD a raiding party arrived off the mouth of the Guadalquivir. They may have made another attempt on Seville before sailing through the Straits of Gibraltar and raiding the coast attacking Algeciras, Cartama, Malaga, and as far inland as Ronda before heading off to Murcia and then over to the Balearic Islands and north Africa. Historians calculate that the Vikings started this raid with over 100 ships. They lost all but 38 in Asturias and a further 18 to the fleets of Cordoba. Fewer that 20 returned home, packed with gold.

Viking raids continued to be a problem for Spain until the middle of the 11th century but after the raids of 860 AD, no major Viking incursions occurred in al-Andalus, they were confined to the north of Spain, Galicia and Asturias.