The dolmens of Antequera, Menga, Viera and Romeral, and the anthropomorphic rock formation Peña de los Enamorados, were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list

By Nick Nutter | Updated 4 Jun 2023 | Málaga | Places To Go |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

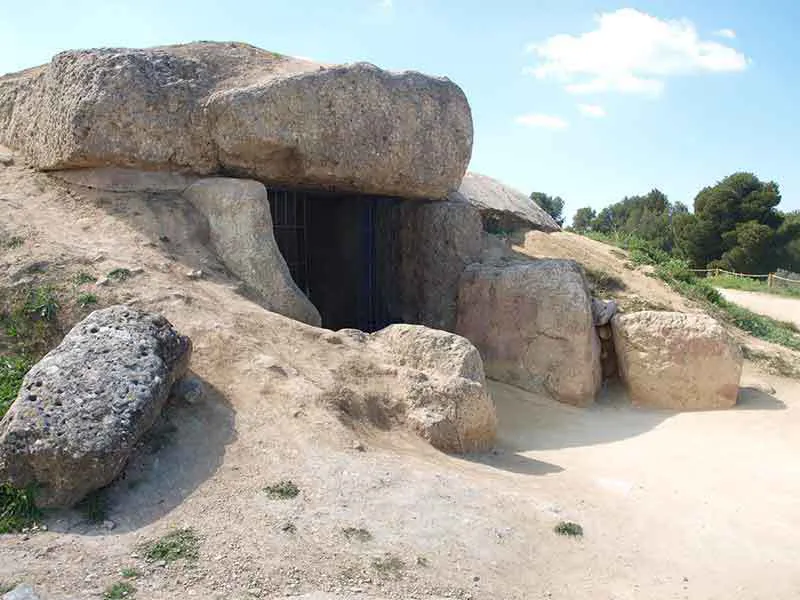

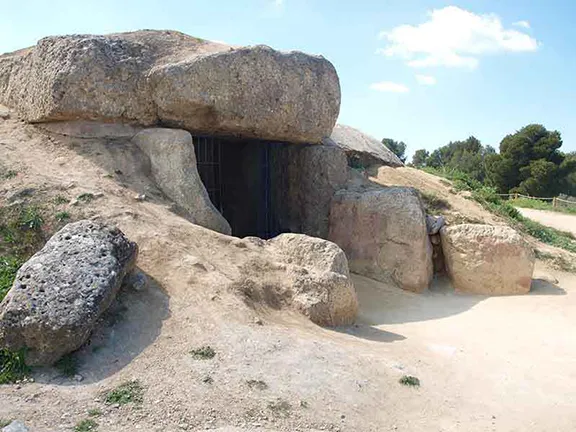

The emblematic entrance to Menga

On the 15th July 2016 the dolmens of Antequera, Viera, Menga and Romeral, together with the mountains of El Torcal and Peña de los Enamorados were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list. This is their story.

Granite outcroppings Extremadura

About 10200 BC or even earlier, the Natufian people in the Middle East who had developed a dependence on wild cereals in their diet and a relatively sedentary lifestyle started to sow cereal seeds saved from previous years. It was the beginning of the Neolithic period. Over a period of 4,000 years, the Natufian people percolated west moving just a few kilometres generation by generation, sometimes coming into contact with the existing hunter-gatherer people, sometimes moving into empty territory. By the time the Neolithic skills arrived in Andalucia, 6000 BC or thereabouts, animal husbandry, sheep, goats and pigs, had been added to the Neolithic skill set. That is not to say that hunting and gathering did not supply a large part of the Neolithic farmer’s diet. It did. Nor did the Neolithic farmer immediately settle down in one place and build a village.

The typical Neolithic family consisted of a couple of dozen members. They moved about the landscape with their few animals, they used caves and temporary outdoor shelters, sowing seeds when they came across suitable areas of land and then leaving the seeds to grow unassisted. They had animistic beliefs, seeing themselves as part of the landscape, no different to the plants and animals they observed with no real difference between the spiritual and material world. They had a cyclical view of life influenced again by what they observed around them. They also believed in agency, that every event, even every object and rock formation had deliberate design.

Periodically families would congregate in one place. They would exchange women and breeding animals and perhaps even surplus foodstuffs if one family had suffered a bad growing year. They would negotiate access to vital supplies such as water and salt if they were fortunate enough to have such a resource in their territory. Exotic objects from far away, seashells, yellow flint and worked axes would change hands, perhaps as part of the bride price, perhaps to create a future obligation or repay one. All these habits are observed in traditional hunter-gatherer societies whose way of life has not changed in the last 10,000 years. Then the families would disperse back into their own territories and adopt their normal autonomous lifestyle.

Peña de los Enamorados as seen from Menga corridor

About 4800 BC something happened in what is now central Portugal that encouraged the local inhabitants, for the first time ever, to consciously make their mark on the landscape. Perhaps it was a realisation that they, in part, were controlling their own destiny. Perhaps the Neolithic population had grown to such an extent that good land was becoming a commodity that had to be marked as owned by particular families. The first menhirs, upright standing stones, appeared and soon afterwards the first dolmens, burial chambers made out of large stones and then buried beneath a mound of earth. Perhaps those first architects were influenced by the granite outcroppings you see in central Portugal and Extremadura in Spain. Seeing them today you could easily believe they were handcrafted so surreal are they in their setting. More likely they were imitating the massive shell middens that the Mesolithic people around the Tagus estuary had created in which they buried their dead.

The entrance and tumulus of Viera

The question of what motivated these people to build monuments to their ancestors is not only interesting but a continued debate in academic circles. Traditional societies today tend to revere their ancestors and look after them well into old age. They are valued for their knowledge and experience, living encyclopaedias in the absence of books or any other written material. It is the old people that can remember how to survive in bad times, which plants to eat when few are available, which springs are the last to dry up, where animals migrate to and when, survival skills such as how to knap flint, how to make fire and so on. This knowledge is passed down to their offspring. Traditional societies often believe that even after death an ancestor is still there in spirit and still able to benefit the family. It stands to reason that the family with the oldest or wisest or most knowledgeable elders is likely to command respect, even obedience, from other families.

But what was the motivating factor that allowed one family to bring together a number of families in the joint ventures required to build the larger dolmens. Was the actual endeavour a group bonding exercise that affirmed each families membership of a wider group? Was this the first instance of class distinction that would blossom into the societies we know today with all the problems of wealth and power distribution? Did the Neolithic people at that time feel threatened and safer in larger groups that could demarcate their territory? Was available land a scarce resource, forcing the Neolithic people to identify what was theirs? We may never know for sure.

Video By: Julie Evans

El Romeral entrance and tumulus

From Portugal the dolmen building custom spread north into northwestern Iberia and France and from there to the British Isles and southeast into Andalucia and then east to Almeria and beyond, anticipating the later trade and communication networks that would become established. Whatever the belief behind the custom the Neolithic people must have considered it worthwhile. Each dolmen required the invested time of dozens of people, the larger dolmens must have involved hundreds, each with families of their own. A recent experiment by Granada University involved moving a 13.5-ton menhir a few metres just using manpower, ropes, levers and wooden rollers. It took one hundred students to perform the task. One of the capstones in the Menga dolmen is estimated to weigh 250 tons.

That three dolmens of the size of Viera, Menga and El Romeral should be situated in such close proximity is unusual. It perhaps indicates that the fertile land surrounding the site not only supported a large number of families but that one or a succession of those families exerted a great deal of influence over the others for a considerable length of time.

About 5000 BC the area was much wetter than it is now. Shallow lakes and ponds were interspersed with stands of ash, alder and hazelnut trees. The river Guadalhorce ran through the area with a number of tributaries feeding into it. On the slopes of the mountains were pine and oak forests. The undercover was rock roses, thyme, rosemary, daisies, dandelions, thistles and grasses. There was abundant game to be had as well as plants, tubers and berries to forage. The Neolithic hunter-gatherers of the era lived in the many cave sites to be found in the Sierra de El Torcal, the Loma de Guerrero, the Cuesta de el Romeral, the Peña de los Enamorados and the Sierras of La Camorra and Humilladero. Archaeologically invisible are the many open-air sites that would have been temporarily occupied in the valleys and plains.

Carbon 14 dates obtained from Menga indicate it was built sometime before 3500 BC, maybe as long ago as 3790 BC, making it potentially the oldest of the three dolmens.

Strictly speaking, Menga is a corridor tomb or passage grave. The corridor is shaped like a funnel, increasing in height and width as it penetrates the mound so that the final 'chamber' is an expanded part of the corridor.

It is the largest in Europe at nearly 30 metres long with not only the aforementioned 250-ton capstone but an upright orthostat weighing 180 tons. There are three different sections, an open corridor leading to a passage covered by four capstones that in turn leads to an oval-shaped funerary chamber covered by one capstone. The four rearmost capstones are, uniquely, supported on the interior by three upright stone columns. There is also a round vertical shaft descending 19.5 metres down beyond the rearmost upright that may be original or may have been excavated in the 19th century. The design is known as a megalithic corridor tomb although there are some elements of a later design known as a gallery tomb. The tomb is orientated towards the northeast and aligns with the Peña de los Enamorados: a mountain formation that is shaped like a human face in repose. The whole was covered in a tumulus some 50 metres in diameter.

Carbon 14 dates obtained from Viera indicate it was built before 3000 BC and may be as old as 3600 BC. It seems likely that it was built soon after Menga.

Viera is a corridor tomb some 21 metres long. Each side of the tomb was made up of 16 slabs of which 14 are preserved on the left and 15 on the right. Five of the capstones are intact and there are fragments of another two. Three or four more capstones are missing. The interior width is 1.3 metres at the entrance and 1.6 metres in the chamber. The chamber is entered through a quadrangular hole cut through a stone slab. The height within the tomb is just over 2 metres. Viera is aligned just south of east which is a common alignment for dolmens in the Iberian peninsula. The whole is covered by a 50 metres diameter tumulus.

The two dolmens, Menga and Viera are just a few metres apart. El Romeral is about 1 kilometre away.

There are no carbon 14 dates for El Romeral. It is estimated from dates of similarly designed structures at Los Millares to have been built around 2500 BC. In fact, there are so many similarities between the tholoi at Los Millares and El Romeral it has been proposed there was a direct link between the two areas.

El Romeral is a tholoi, a false cupola tomb. The 26-metre long corridor is constructed of masonry with a roof of eleven slabs. The height is 1.94 metres. The chamber at the end of the corridor is circular with a diameter of 5.2 metres and a height of 3.75 metres. The dome is capped by one large capstone. At the far end of the chamber is a low masonry built corridor leading to a much smaller domed chamber. The complete length of the tomb is 34 metres and it is covered by a 75-metre diameter tumulus. The tomb is orientated towards the south southwest facing the highest part of the Sierra de El Torcal.

Unfortunately, no grave goods have been found in any of the three dolmens. They were probably plundered during the Roman period. Nor is it possible to infer how many people were interned in the dolmens, their remains are long gone.

A visit to the dolmens of Antequera and the associated visitors centre is a good way to start appreciating the scale of the megalithic landscape of Andalucia that includes standing stones – menhirs, stone circles – cromlechs, small stone burial chambers – cysts, artificial caves – hypogeum and cave and rock shelter paintings and engravings as well as hundreds of dolmens large and small.

Located at the heart of Andalusia in southern Spain, the site comprises three megalithic monuments: the Menga and Viera dolmens and the Tholos of El Romeral, and two natural monuments: La Peña de los Enamorados and El Torcal mountainous formations, which are landmarks within the property. Built during the Neolithic and Bronze Age out of large stone blocks, these monuments form chambers with lintelled roofs or false cupolas. These three tombs, buried beneath their original earth tumuli, are one of the most remarkable architectural works of European prehistory and one of the most important examples of European Megalithism.

For opening times of the Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera, click here